In my last two posts (here 1 and here 2) I discussed line layouts, including the famous U-line. In the last post of this small series, I would like to wrap up the line layout discussions, looking at merging material flows and other things.

In my last two posts (here 1 and here 2) I discussed line layouts, including the famous U-line. In the last post of this small series, I would like to wrap up the line layout discussions, looking at merging material flows and other things.

Merging Material Flows

The above line layouts are normal straight-line layouts. However, there may also be merging of manufacturing lines. Less commonly there may even be manufacturing lines that split up temporarily or permanently to make different products (often in chemical processes, where for example you break down crude oil into its components). Here, too, you have different possibilities, although the limitations and advantages are not as significant as with the main line layout.

The general advantage of having a sub-assembly or secondary manufacturing line merge with the main line directly is that there is no warehouse speed needed in between. If the output of the secondary lines matches the demand of the main line, you can establish a good material flow with little inventory. Overall it will be a very lean system, allowing one-piece flow and smaller lot sizes between the sub-assemblies and the main line. For some good examples, see my post Toyota’s and Denso’s Relentless Quest for Lot Size One, where they even managed to put an aluminum foundry in the overall assembly system, having the required output and also the needed flexibility to provide parts just on time (or Just in Time – JIT).

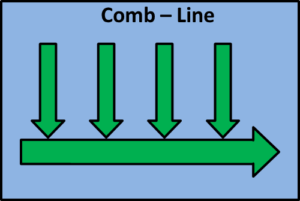

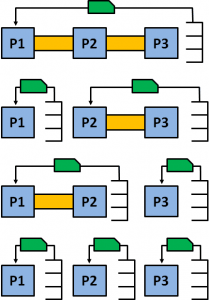

Comb-Line

Merging different sub-assemblies or sub-manufacturing lines into one main line may be done using a comb-style design. All secondary lines merge from one side of the line. I have seen this, for example, with manual assembly lines, where the operators of the main line stand on the same side as the sub-assembly lines. Besides a smooth material flow, this also created a close-knit group, and occasional problems caused by the sub-assembly line were resolved quickly. Due to the close interaction, all involved operators had a steep learning curve to reduce problems.

Merging different sub-assemblies or sub-manufacturing lines into one main line may be done using a comb-style design. All secondary lines merge from one side of the line. I have seen this, for example, with manual assembly lines, where the operators of the main line stand on the same side as the sub-assembly lines. Besides a smooth material flow, this also created a close-knit group, and occasional problems caused by the sub-assembly line were resolved quickly. Due to the close interaction, all involved operators had a steep learning curve to reduce problems.

The other side of the comb-line may be used to bring additional material to the main line, as it is easily accessible for fork lifts and milk runs from that side.

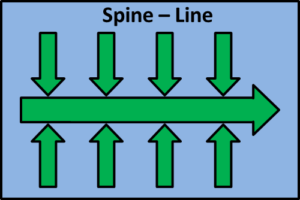

Spine-Line

The spine-line, sometimes also called fishbone-line, has sub-assemblies coming from both sides. I have seen this at bigger assembly lines, where operators were working on both sides of the main line. It has similar advantages as the comb-line, except that it may be more difficult to bring larger materials to the line using forklifts or milk runs, as both sides are occupied by sub-assemblies. Still, also a possibility.

The spine-line, sometimes also called fishbone-line, has sub-assemblies coming from both sides. I have seen this at bigger assembly lines, where operators were working on both sides of the main line. It has similar advantages as the comb-line, except that it may be more difficult to bring larger materials to the line using forklifts or milk runs, as both sides are occupied by sub-assemblies. Still, also a possibility.

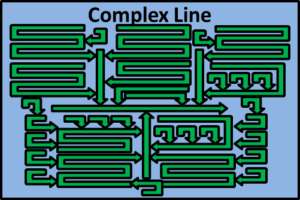

Segmenting a Value Stream

A value stream is usually a system with many, many branches. For designing a good system, it is necessary to be aware of these branches. Please note that here I talk only about how to determine segments, not if they should be decoupled using inventory and supermarkets, or if they should be attached using one-piece flow. Below are a number of suggestions and considerations that may play a factor for creating different segments of the line.

- Merging parts: This is of course the biggest reason. Whenever two parts merge, then you have a merge in the value stream. Hence, two material flows come together. Again, how you manage this is not yet the question, but at this stage only the realization that they do.

- Vastly different production techniques: For example, having a foundry within the assembly line is quite difficult. For a good example, see Toyota’s and Denso’s Relentless Quest for Lot Size One, mentioned above.

- Negative technical influences: Sometimes, one process may negatively influence another process. For example, if you have a 5,000-ton stamping press next to a high-precision milling operation, the high-precision milling won’t be that high precision anymore. (The stamping press doesn’t mind though).

- The “My Turf” factor: Often, production is in different plants, maybe within the same company, maybe with external suppliers. In this case turf wars can play a factor. Few plant managers are willing to give away part of the production, since production means employees, revenue, and, after all, power. Depending on how important this is to you, and on your level of influence, you can fight it or you can accept it. As usual, you can’t fight everybody, and you should avoid fights that you would lose.

Segments: Decoupling vs. One-Piece Flow

Larger assembly systems may quickly become too complex to have all on one single line. While it would be nice to have a one-piece flow between every part of the value stream, it may be too much to handle in many systems. Even Toyota has buffers between segments of their value stream. Overall, it usually makes sense to break the entire value stream down into smaller systems.

Larger assembly systems may quickly become too complex to have all on one single line. While it would be nice to have a one-piece flow between every part of the value stream, it may be too much to handle in many systems. Even Toyota has buffers between segments of their value stream. Overall, it usually makes sense to break the entire value stream down into smaller systems.

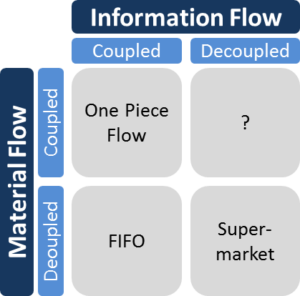

Above we looked at where we could have segments. Now we want to look at where and how we decouple the segments. You can decouple the material flow, and can also decouple the information flow. You have the following options:

- No decoupling: This would be one-piece flow. The segment produces a part exactly when the subsequent segment needs it. This is often quite efficient, but it is also the most difficult to implement.

- Decouple material but not information flow: The prime example here is FiFo lines. There is a buffer inventory between the segments to cover fluctuations in speed, but the segments are still part of the same information loop. A common example is seat manufacturing for automotive. There is a buffer, but the decision to manufacture a car is automatically also a decision to manufacture the matching seat, and the seat has to be ready in time when the car needs it.

- Decouple material and information flow: The prime examples here are supermarkets. Only if the subsequent segment uses a part does the preceding segment start to reproduce. Unfortunately, supermarkets work only for mass production, but not very well for individual made-to-order parts. For made-to-order parts, this decoupling of both material and information flow is usually not preferred, as it takes too long to produce the product. Ideally, you make components for the product simultaneously, which would require a coupled information flow. If you start producing only when you need it, then your overall lead time may become unfeasibly large.

- Decouple information flow but not material flow: I don’t think this is even possible. This would mean that the part has to be ready just when you need it, but you don’t tell the preceding segment when you need it. I just added this here for completeness sake. Ignore it.

So, when and where should you decouple and break it down into different value streams? You would have to find a compromise. Of course, no decoupling can be most efficient, but it is also most difficult to manage (and if you don’t manage it well, the efficiency can also be much worse than other systems). The exact answer depends on your system. For some very related posts that may give you suggestions, see Ten Rules When to Use a FIFO, When a Supermarket – Introduction and Ten Rules When to Use a FIFO, When a Supermarket – The Rules. Also very related are The Three Fundamental Ways to Decouple Fluctuations, Determining the Size of Your FiFo Lane – The FiFo Formula, and The FiFo Calculator – Determining the Size of your Buffers.

So, when and where should you decouple and break it down into different value streams? You would have to find a compromise. Of course, no decoupling can be most efficient, but it is also most difficult to manage (and if you don’t manage it well, the efficiency can also be much worse than other systems). The exact answer depends on your system. For some very related posts that may give you suggestions, see Ten Rules When to Use a FIFO, When a Supermarket – Introduction and Ten Rules When to Use a FIFO, When a Supermarket – The Rules. Also very related are The Three Fundamental Ways to Decouple Fluctuations, Determining the Size of Your FiFo Lane – The FiFo Formula, and The FiFo Calculator – Determining the Size of your Buffers.

Ride the Learning Curve

In many companies, I see the expectation that it has to be perfect from the beginning. No, it doesn’t! Toyota is well known for its strive for perfection. But this applies to products, which it usually produces in large quantities. A production line is usually unique. Hence, Toyota aims to have a line that is good but allows further optimization. After the line is up and running, Toyota works on improving and fine-tuning the system. For a good example on how the line changes over time, look at The Evolution of Toyota Assembly Line Layout – A Visit to the Motomachi Plant.

In many companies, I see the expectation that it has to be perfect from the beginning. No, it doesn’t! Toyota is well known for its strive for perfection. But this applies to products, which it usually produces in large quantities. A production line is usually unique. Hence, Toyota aims to have a line that is good but allows further optimization. After the line is up and running, Toyota works on improving and fine-tuning the system. For a good example on how the line changes over time, look at The Evolution of Toyota Assembly Line Layout – A Visit to the Motomachi Plant.

While this optimization is necessary, it is unfortunately not glamorous. In the West, you can make a career by building lots of lines. Improving the lines is, however, something that is not really noticed very much. If you do your job right, nothing (bad) really happens. Hence, you can’t even shine through firefighting, since you prevented the problems from happening in the first place. Overall, this line optimization happens, in my opinion, way too little in the West. If you can, do ride the learning curve and optimize your system!

Anyway, this concludes my series of articles on line layouts. I hope this was interesting for you. Now, go out, optimize your line, and organize your industry!

Thank you, Christoph. The whole coupling (or decoupling) between information and material flow is interesting and I will read more about it through the additional links provided.

Thank you, Christoph,

From my point view line is more like office area for frontline operators,we should consider consultant with shopfloor people together to finalize faster,better,cheaper layout.that also show our respect to these group.also some campany use manual simulation (cardboard) or software simulation to see the ease and impact.The most lean layout I see in my ordinary life is china street vendor who supply breakfast to people is rushing for work.small scale size,mobile cart,material presentation,one people manipulation with multi-skill, controlled invenroty with mixed pull and push,safer workplace and good 5S.so wonderful system and simplier.But in reality we encouter different stakehold and need balance short term and long term constraint.It is not easy and workable.

I am looking forward more inspiring strings and perspective from you and your practise.

one question how can you develop brilliant skill to illustrate so many vivid and easy

understanding illustrations which is sparking our mind:-0)

chinese love saying more than drawing more

all the best

Hi Frank, I do indeed spend quite some time on illustrations. My own I make with power point (3 years McKinsey, and you learn a lot about power point 🙂 ). For the others I use google image search for inspiration, and then I look for similar images that are available under a suitable license.

Thanks Chris and I am also hands-on person and unfortunaty we here block google so we have to use baidu which a lots of ads on it

anyway good thoughs and good idea!

Thank you very much Chris for sharing your knowledge!