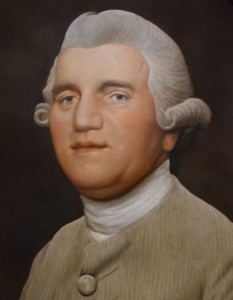

The British potter Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was not only a ceramic artist, but also on the forefront of the Industrial Revolution. Wedgwood brought science into the manufacturing process. He also introduced work standards, time sheets, and many other methods that are common in the modern-day workplace.

The British potter Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was not only a ceramic artist, but also on the forefront of the Industrial Revolution. Wedgwood brought science into the manufacturing process. He also introduced work standards, time sheets, and many other methods that are common in the modern-day workplace.

While experiments to gain knowledge were already well known in science, craftsmen still followed the old traditions and rarely improved their craft. Josiah Wedgwood was one of the first industrialists who used this scientific method of experimenting and collecting data to propel his wares to an never-before-seen level of quality. Combining this with his keen business sense, he and his firm prospered, and the works of his firm are still highly regarded even today.

Personal Life

Wedgwood was born in 1730 in Burslem, Staffordshire, as the eleventh (!) child of Thomas and Mary Wedgwood. He was the fourth generation of a series of potters. While he was initially a skilled potter, smallpox almost killed him and permanently crippled him. He no longer could use one of his knees and needed crutches. Hence he also could no longer operate a potter’s wheel. Later in his life, his right leg even had to be amputated, in 1768, due to smallpox. (Please note that general anesthesia was invented only eighty years later, although his friend Priestley [see below] experimented with NO2 … but with results only seven years after Wedgwood’s leg was chopped off with a bone saw). Hence Wedgewood focused more on sculpting and design rather than making traditional pottery.

In school he was skilled at math, and was lucky to have a teacher who was skilled in the scientific method and taught him the value of experiments and data. He worked first with his older brother Thomas Wedgwood, and thereafter with Thomas Whieldon (1719 – 1795), who soon became his partner. Whieldon was a creative thinker and liked to experiment and to try things out, significantly influencing Wedgwood.

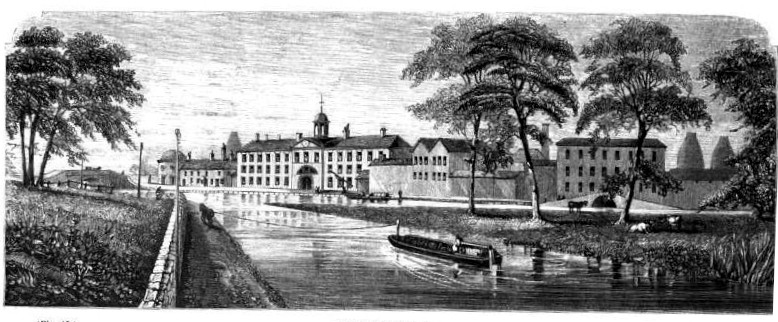

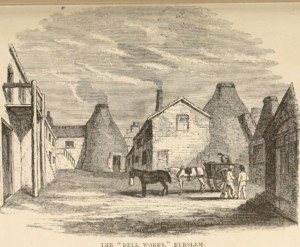

Eventually Wedgwood established his own workshop in Ivy Works in the town of Burslem in 1759 at the age of 29. He moved his expanding operations to a larger factory, Bell Works, in 1762 in Burslem, and started his famous Etruria Works in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England, in 1769. He married his third cousin in 1764 and had eight children. One of his grandchildren was Charles Darwin. He died at home in 1795, aged 64, probably due to cancer.

Work Organization

First of all, inspired by Matthew Bolton’s Soho factory, he organized his workshops in the flow of the material. His workshop had five major departments, and they were arranged so that the clay traveled from the docks at the river in a circle back to the docks again as finished products. Contrary to modern-day lean manufacturing, however, he was not controlling the inventory but produced as much as possible and had quite large inventories.

Wedgwood strongly believed that a division of labor and subsequently using many different separate process steps is much more efficient and profitable than the previous generalist potter. Hence he organized his workshops in many small tasks, and his workers were assigned specific workplaces. They were not permitted to “wander around” between different tasks, as had been common before. He even had separate entrances for separate processes within the same building.

The speed of each task was also matched to the overall speed of the system (a takt time, if you will). Subsequently the workers became specialists, and therefore also much better and faster at their specialty than the generalist potters before. Out of 278 workers in 1790, only five were “odd men” without a specific assignment. He also created written work instructions for each task, the precursor of modern work standards. Hence he, in his own words, managed “to make Artists… (of)… mere men,” to “make such machines of the Men as cannot err.”

He also found that training older workers was much more difficult, and they tended to resist his new ways. Subsequently he preferred to train young employees to shape them to his vision. Overall, 25% of his workers were apprentices. He also employed women and girls, but also paid them less than the men and boys.

Workers had to show up on time, and Wedgwood introduced the first system to track time using a bell in 1762 in his correspondingly named Bell Works factory. The bell was rung at 5:45AM, an hour before work to wake people up, at 8:30 for breakfast, at 9:00 for the end of breakfast, and so on. He used pieces of paper with the names of the employees to track time and attendance, the precursor of the modern timesheet. This was very much disliked by the older, traditional employees, but they liked his ban on drinking even less. Still, Wedgwood was never able to fully control the work times (many modern-day shop floor managers surely understand. If not, go to the shop floor five minutes before the break and observe the “work”). Potters regularly took whole days of leave, e.g. for funerals or festivals.

To keep discipline, Wedgwood was very stern and often feared by his employees. When a riot happened in 1783, he summoned the military and had one of the men hanged. Keeping this discipline was also difficult, as he had to travel often to other cities on business, and his written rules were usually ignored. He was one of the first who experimented with introducing middle managers, but had difficulties finding suitable people. Experienced workers in a supervisor role continued to ignore the rules. Eventually a nephew of his, Thomas Byerley (1747 –1810), was able to take over, but even then Wedgwood’s absence was bad for production. During his two-week honeymoon, for example, production stopped completely. Nevertheless, he was probably one of the first to introduce the foreman to production.

His workshops were also meticulously clean. Even though the effect of lead poisoning was still not well understood (and few industrialists cared), Wedgwood had more-stringent rules for the lead-glazing room. Workers had to keep the room even cleaner than the rest of the factory, were not allowed to eat in the room, used protective clothing, and used a wet sponge instead of a brush for applying the coat to reduce dust. Similar measures were taken at the grinding of flint, the dust of which could damage the lungs.

Despite his stern rule, working for him was popular, pay was good, housing was clean, and he took care of the health of his people. While he still ruled like a king (like most industrialists of his time), he was a comparatively good employer. Hence, few people left (despite numerous tries by the competition to hire his workers in order to duplicate his success). In his own words, he turned “dilatory drunken, idle, worthless workmen” in 1765 into “a very good sett of hands” by 1775.

Accounting

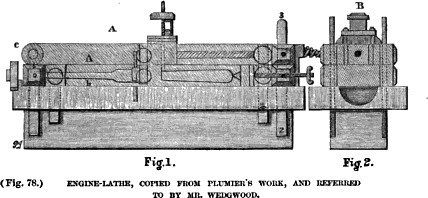

Wedgwood also kept track of expenses and profits. Highly unusual for the time, he had an accounting system rather than just working and hoping that the profit would materialize. He knew the cost of every step of his value stream. He experimented with a pay-by-piece remuneration, but found the resulting quality insufficient. He understood the difference between fixed assets and variable costs, and increased mechanization of production. For example, Wedgwood was the first to use a lathe in pottery production.

Scientific Approach

Influenced by his school teacher and his first partner, Whieldon, Wedgwood was familiar with the scientific method, using experiments and measurements to further knowledge in his field. He performed countless experiments, measuring weights and ingredients, tracking the position in the kiln, and recording the results of the pottery. To measure the temperature, he invented a high-temperature thermometer – a pyrometer, or now called Wedgwood scale – where the temperature is measured based on the expansion of clay.

His notebook was filled with huge amounts of data. He even made models predicting the outcome of his experiments. He studied chemistry and materials, and sampled and experimented with different clays and other minerals both for the pottery and for the glaze. Due to his research, he was able to maintain a consistent quality and color. At that time, if you broke one of your dishes within a larger set from another potter, you could of course order a replacement. But there was no guarantee at all that it would have the same shade of color. In the worst case, you ended up with one of your plates looking different.

He also exchanged ideas with Joseph Priestley (1733 – 1804, discoverer of oxygen), and met and interacted with Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790, one of the US Founding Fathers). He bought a lathe from Mathew Boulton (1728 – 1809) and became a close friend to him. They cooperated to create metal implements in ceramic vases. He was also familiar with Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin; canal-builder James Brindley; industrialist Richard Arkwright; and many more of the who’s-who of eighteenth-century science and industry.

He was one of the principal members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, so named since they met during a full moon – whose extra light made it easier to walk home late at night. These meetings aimed to exchange and discuss ideas, and the society existed for around fifty years. Many of these irregular members are still well known today, including James Watt (steam engine), Matthew Boulton (Watt’s partner), Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles Darwin), Joseph Priestley (discoverer of oxygen), John Wilkinson (famous ironmonger), Joseph Black (discoverer of magnesium), Benjamin Franklin (US Founding Father), and many more.

Economic Success

In 1769, Wedgwood partnered with Thomas Bentley (1731 – 1780), a local merchant. Soon Bentley handled the sales in London, and Wedgwood the production in Etruria.

In 1763, Queen Charlotte ordered Wedgwood pottery, which he then marketed as “Queens Ware.” Anything made for the queen was exhibited for advertising beforehand.

They created two different lines of pottery, high-quality hand-crafted and hand-painted “ornamental ware” for the elite, and lower-quality “useful ware” made using simple molds for the middle class. The ornamental ware was made in Etruria, and the useful ware in the Bell Works.

The high-end products were not always profitable. First, he gave away thousands of items for free to nobility. Second, even if it was a sale, how do you force a king to pay a bill? Nevertheless, it was excellent advertising and helped sell his other products to the middle class.

He also advertised in newspapers, and even spread false rumors of upcoming shortages to increase sales. He printed his first catalog in 1773. Due to the quality and popularity of his goods, he was even able to sell his goods to China (usually it was the other way round).

Legacy

![]() Wedgwood is known for two things: First, for the artistic quality of his wares. His company still exists, and is still positioned in the premium segment for ceramics. Second, and the focus of this post, his scientific approach to manufacturing. As Winslow Taylor is the father of scientific management, so is Wedgwood the father of scientific manufacturing. His approach to measure, experiment, and improve quality, as well as his rigorous organization of his factories, was centuries ahead of others. He was probably the first to use controlled experiments in manufacturing. Hence, I am happy to have the opportunity to commemorate him in this blog post, which turned out much longer than usual. Now go out, understand your processes, and organize your industry!

Wedgwood is known for two things: First, for the artistic quality of his wares. His company still exists, and is still positioned in the premium segment for ceramics. Second, and the focus of this post, his scientific approach to manufacturing. As Winslow Taylor is the father of scientific management, so is Wedgwood the father of scientific manufacturing. His approach to measure, experiment, and improve quality, as well as his rigorous organization of his factories, was centuries ahead of others. He was probably the first to use controlled experiments in manufacturing. Hence, I am happy to have the opportunity to commemorate him in this blog post, which turned out much longer than usual. Now go out, understand your processes, and organize your industry!

P.S.: If you want to learn more, I can recommend The Wedgwood Museum in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England.

Hi Christoph,

Nicely written article… would never have know about Josiah Wedgwood’s contribution to the practice of manufacturing had you not written this.

Hello Christoph! Thank you for writing about such a great and inspiring man! What a great model for today’s Entrepreneurs. Would love to learn about his accounting system based in double-entry bookkeeping. If ever you come across this information, I’ll be more than happy to know of it.

Kindly,

Terri

Hi Terri, bookkeeping is unfortunately not my specialty. But it seems that double accounting is nowadays common https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Double-entry_bookkeeping .

An excellent article.

I am from the Potteries area and my father was born in Burslem so I can relate to your article. Josiah Wedgwood was a key leader in the early innovations of the Industrial Revolution, including his involvement with James Brindley in the opening of early canals, which started a revolution in the efficient transport of goods and the wealth building of the nation.

I’m an innovator myself, and may possibly be distantly related to the great man, although I don’t have any solid evidence to prove that. Josiah Wedgwood is said to have at one time been the richest man in England, leaving the aristocrats dumbfounded because they could not understand how a mere tradesman could be as wealthy as a landed gentleman.