Changeover sequencing helps you to produce more efficiently with smaller lot sizes, less inventory, and/or less changeovers. But despite a good changeover sequence, sometimes things blow up in your face. Your supplier does not deliver, your customer wants more than you planned, or your main process went belly-up and is waiting for repairs. In any case, something is forcing your hand and messing up your changeover sequence, or more generally your entire production sequence. What do you do? Well, depending on what happened, you may have options to mitigate the damage. This first post will look at mishaps originating from your supplier, and the next post will look at difficulties originating from your customer or even from your own system.

Changeover sequencing helps you to produce more efficiently with smaller lot sizes, less inventory, and/or less changeovers. But despite a good changeover sequence, sometimes things blow up in your face. Your supplier does not deliver, your customer wants more than you planned, or your main process went belly-up and is waiting for repairs. In any case, something is forcing your hand and messing up your changeover sequence, or more generally your entire production sequence. What do you do? Well, depending on what happened, you may have options to mitigate the damage. This first post will look at mishaps originating from your supplier, and the next post will look at difficulties originating from your customer or even from your own system.

Introduction

I have written a lot on changeover sequencing, usually using ice cream as an example. I explained the basics in Changeover Sequencing Part 1 and Part 2, talked about prioritization, and also discussed fluctuations, in addition to many posts on how to do changeovers or reduce changeover duration. In this post I will look at what to do if something goes wrong. I loosely structured this using source-make-deliver (i.e., problems with your supplier, in your own process, and with your customers).

I have written a lot on changeover sequencing, usually using ice cream as an example. I explained the basics in Changeover Sequencing Part 1 and Part 2, talked about prioritization, and also discussed fluctuations, in addition to many posts on how to do changeovers or reduce changeover duration. In this post I will look at what to do if something goes wrong. I loosely structured this using source-make-deliver (i.e., problems with your supplier, in your own process, and with your customers).

Problems with Source

Let’s have a look at the first example: you have problems with your source of materials (i.e., your suppliers). In most cases this means that you are not getting what you need, or at least not in a timely fashion. This could be due to problems at the supplier, delays during shipping, your supplier going bankrupt, and many other things. It could also happen due to reasons on your side, like you don’t have the money to pay, you messed up or forgot your own orders, or you pissed off the supplier enough that he no longer wants to deal with you.

Let’s have a look at the first example: you have problems with your source of materials (i.e., your suppliers). In most cases this means that you are not getting what you need, or at least not in a timely fashion. This could be due to problems at the supplier, delays during shipping, your supplier going bankrupt, and many other things. It could also happen due to reasons on your side, like you don’t have the money to pay, you messed up or forgot your own orders, or you pissed off the supplier enough that he no longer wants to deal with you.

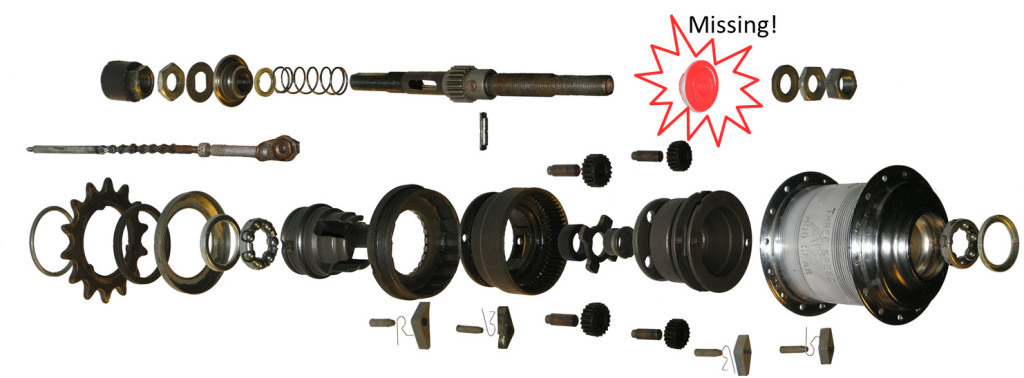

In any case, you miss some of the material and parts you need, or you can foresee that you will not get them on time. Even if it is only a cheap part missing, it has the power to stop your entire production. If you lack an O-ring worth less than 1 cent, you cannot produce, ship, deliver, and get paid for an entire product worth potentially millions. One obvious step is now to escalate to try to get parts earlier. Pay a premium, try to get other suppliers, do air freight instead of the much cheaper ocean shipping (that is supposedly how airlines make most of their money), and many more. In foresight you may have already established a two-supplier system for all your parts instead of having a single source. But this is not the focus of this blog post.

In any case, you miss some of the material and parts you need, or you can foresee that you will not get them on time. Even if it is only a cheap part missing, it has the power to stop your entire production. If you lack an O-ring worth less than 1 cent, you cannot produce, ship, deliver, and get paid for an entire product worth potentially millions. One obvious step is now to escalate to try to get parts earlier. Pay a premium, try to get other suppliers, do air freight instead of the much cheaper ocean shipping (that is supposedly how airlines make most of their money), and many more. In foresight you may have already established a two-supplier system for all your parts instead of having a single source. But this is not the focus of this blog post.

Because there is another thing you can do: namely, fine-tune your production sequence. This won’t give you more parts, but it will help you to use the remaining parts you have for the best outcome. You need to figure out what products need the parts that are in short supply, and then prioritize by end products. Figure out which products and how many of them are most important with the parts you have. The priority is usually related to profit, but includes such hard-to-guess costs of declining customer relations if they do not get the part. Often, companies opt to keep their larger customer happy and are willing to drop the small-fry customers first.

For changeover sequencing, you can still optimize the sequence of the prioritized products to reduce changeover time and effort. You do not have to produce your products strictly in order of their priority, but can switch these prioritized products to reduce the changeover effort. Just don’t schedule any non-prioritized products in the sequence just because it fits nicely. Your limitation is not the capacity but the materials!

It may also matter how many materials a part needs. Assume you have two products, one that gives you a profit of $10 000, the other one a profit of $3000. Both of them are short of the same type of O-ring. At first glance, the $10 000 product would be more important than the $3000 product. However, if the $10 000 product needs ten O-rings, and the $3000 product needs only one, then you could make a profit of $30 000 by making ten of the $3000 products instead of profiting $10 000 by producing only only one of the $10 000 product. Overall you try to maximize the profit and minimize the losses with the available materials.

It may also matter how many materials a part needs. Assume you have two products, one that gives you a profit of $10 000, the other one a profit of $3000. Both of them are short of the same type of O-ring. At first glance, the $10 000 product would be more important than the $3000 product. However, if the $10 000 product needs ten O-rings, and the $3000 product needs only one, then you could make a profit of $30 000 by making ten of the $3000 products instead of profiting $10 000 by producing only only one of the $10 000 product. Overall you try to maximize the profit and minimize the losses with the available materials.

In some extreme cases, you could also take already completed products apart to extract the critical parts for other, more-important end products. However, this makes everything more expensive and damages your other, less-important product. I once was at a manufacturer of large industrial pumps, where the completed pumps included a small plastic bag with a kit of O-rings and screws for the installation. This kit was often short on supply, and they regularly treated their finished goods as a part supply, ripping open the packaging to extract this plastic bag. These pumps were stored outside in (formerly) waterproof packaging, and as a result, these products got wet and started to rust. Hence, every product had to be checked for rust, missing parts, and repackaged before shipping. What a pain, and all for a small bag worth less than $5 for a pump worth thousands. If you take apart existing products to make other products, then the cure may be worse than the disease. Use this approach only as a last resort.

Just for completeness’ sake, there are very rare cases when the problem is not too few parts from the supplier, but too many. This could be due to ordering too much by accident, or a supplier that can force parts on you. In any case, this should not change your sequencing much, as you merely have a larger inventory that you have to manage and slowly reduce by trying to get less until you are back to a regular inventory. Quite an unpleasant fluctuation.

Just for completeness’ sake, there are very rare cases when the problem is not too few parts from the supplier, but too many. This could be due to ordering too much by accident, or a supplier that can force parts on you. In any case, this should not change your sequencing much, as you merely have a larger inventory that you have to manage and slowly reduce by trying to get less until you are back to a regular inventory. Quite an unpleasant fluctuation.

Hence, there are quite a few things to consider when you have supply problems, besides obviously fixing your supply problems. In my next post I will look at problems with make (your own production) and deliver (your customer orders too little or – gosh – too much). Until then, stay tuned, and go out and organize your industry!

what a great article. Thank´s