One successful approach to leveling is one-piece flow leveling, which I would like to talk about today. Another successful approach is capacity leveling. These can also be combined. (But please do yourself a favor and stay a way from a longer fixed repeating schedule EPEI leveling.) As the name already says, you should drive your lot size toward one. In addition to one-piece flow, this approach is also known as single-piece flow or continuous flow.

One successful approach to leveling is one-piece flow leveling, which I would like to talk about today. Another successful approach is capacity leveling. These can also be combined. (But please do yourself a favor and stay a way from a longer fixed repeating schedule EPEI leveling.) As the name already says, you should drive your lot size toward one. In addition to one-piece flow, this approach is also known as single-piece flow or continuous flow.

The Basics: Lot Size One

The Traditional Approach – Large Lot Sizes

The traditional thinking in manufacturing systems is that changeover times are a waste. This is correct, they are a waste. However, the traditional conclusion is to do as few changeovers as possible, resulting in large lot sizes. Unfortunately, this will lead to an even bigger waste: excess inventory! Additionally, it will work against smoothing the production and all its associated benefits. Hence, the example shown below is not very lean.

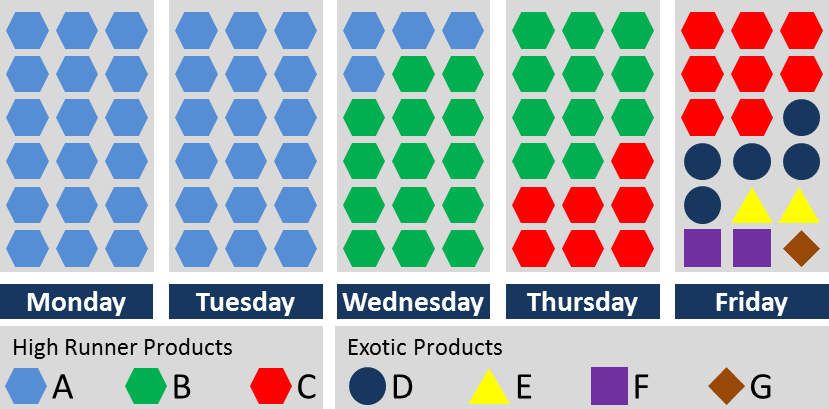

The Wrong Way: Fixed-Sequence EPEI Leveling

One approach often used to change this is to create a repeating pattern. I have explained the details of this approach in my post on the Theory of Every Part Every Interval (EPEI) Leveling, Also Known as Heijunka. However, I have explained even more why this usually fails (The Folly of EPEI Leveling in Practice – Part 1 and Part 2 ). Overall, I would like to strongly advise you against it. Nevertheless, for completeness sake, a possible solution is shown below, even if they rarely work in practice.

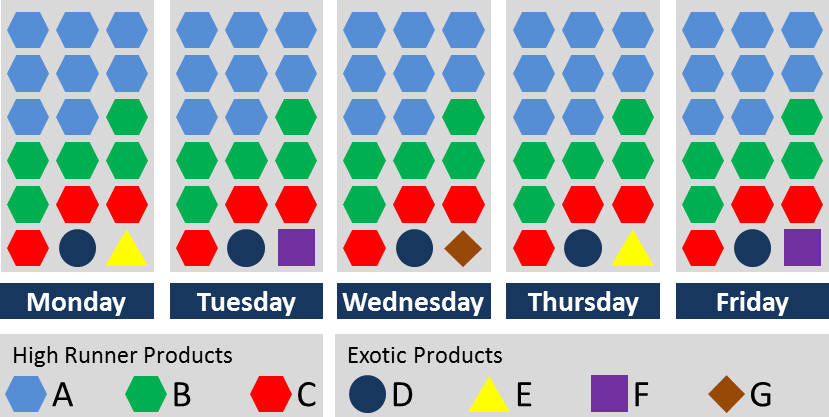

A Better Approach: Lot Sizes for Daily Demand

A much better approach is to reduce lot sizes so you produce every day what you need that day. Just to make sure: You do NOT take the daily average of your weekly/bi-weekly/monthly demand. It is truly what you need to produce today based on the best available data, forecasts, and demands you have today. This includes effects like:

- Rush orders

- Canceled orders

- Changes in demand forecasts

- Suppliers that did not deliver

- Raw material that turned out to be defective/wrong/missing

- Completed products that turned out to be defective/wrong/missing

- Customers begging/threatening/yelling for urgent parts

- Higher-up managers telling you what you must produce right now

- and many more.

Of course, the fewer of these effects you have, the smoother your production will be. But let’s be realistic, you will have at least some of these effects. Based on this best available data (if you can call it that), you should produce every day what is most urgent.

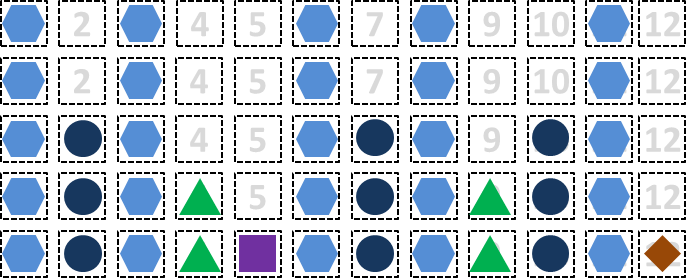

Assuming you cannot yet do one-piece flow, your resulting production plan may look like the image below. Produce whatever is most urgent today, where the lot size is the daily demand of this product.

Of course, for practical reasons, you may still want to pool your exotic parts in larger lot sizes and make them, for example, once per week. The violet square and the brown diamond in the example above have a lot size one. Depending on your system, you may want to pool these together across multiple days and make, for example, three of them once per week. It all depends on the ability of your system.

Of course, for practical reasons, you may still want to pool your exotic parts in larger lot sizes and make them, for example, once per week. The violet square and the brown diamond in the example above have a lot size one. Depending on your system, you may want to pool these together across multiple days and make, for example, three of them once per week. It all depends on the ability of your system.

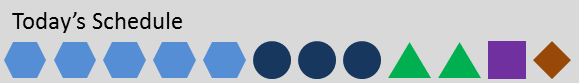

The Lean Approach – Lot Size One, Well Mixed

However, your goal should be to have lot sizes as small as possible, ideally a lot size of one. Furthermore, you should mix your lot sizes as much as possible. One-piece flow leveling does not mean only the ability to do lot size one, but also the mixing of the production sequence so that there are no two similar parts produced together. Hence, it is not the ability to do lot size one, but actually doing only one product before changing to a new product.

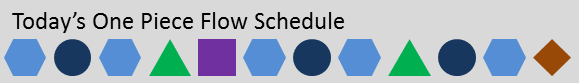

Using the daily schedule from above, the result may look like the schedule below. The total quantities of the parts are still the same, but the sequence is intentionally well mixed.

How to Create the Mix with Lot Size One

I have seen some Excel tools to make a sequence as mixed as possible. If you have one of these (or can make one yourself), it may help in your scheduling. However, in my opinion, it is not strictly necessary. The difference between a perfectly leveled sequence and a nearly perfect sequence is, in my opinion, very small. Even in the example above, you could imagine different patterns that are also similarly leveled. Just try to mix up the sequence as much as possible.

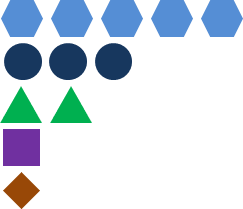

However, here is a basic structured approach to create a good mix that works for products with few common parts (Alternative approaches are available for products that have common parts, which I may cover in another post). Let’s assume that the total production quantity looks like below, producing a total of twelve parts within the planned period (e.g., one day):

We start with the largest volume (the blue hexagons). We want to produce five and have a total of twelve slots. Hence, dividing 12 by 5 results in every 2.4th slot being a blue hexagon. Starting with the first empty slot, this would put a blue hexagon in the 1st, 3.4th (rounded to 3rd), 5.8th (rounded to 6th), 8.2nd (rounded to 8th), and 10.6 (rounded to 11th) slot. The full pattern can be seen further below.

Next we take the dark blue circles. Dividing 12 by 3 circles gives us a circle every 4th slot. Starting with the first empty slot (number 2), we get blue circles in slot number 2, 6, and 10, except that 6 is already taken by a blue hexagon. Hence, instead of in the occupied slot 6, we put the circle in the nearest free slot, in this case slot 7 (although slot 5 would also have been possible).

Similar with the green triangles. Dividing 12 by 2 triangles gives 6 slots between triangles. The first empty slot is 4, hence there is a triangle in slot 4 and 10 – except that slot 10 is occupied. The nearest free slot is number 9, hence the triangles go into slots 4 and 9. The last two exotic pieces then take up the remaining free slots. This gives step by step the one-piece flow pattern as shown below.

Similar calculations can easily be done for other production quantities, and can also easily be implemented in Excel or a similar program.

More Next Week

This post describes how one-piece flow leveling works. Please note that one-piece flow also often refers to a zero (or at least low) WIP approach. In the next post I will discuss how to best implement this one-piece flow leveling, and also what else there is in leveling. In the meantime, go out and organize your industry!

Overview of Posts in this Series about Leveling

- Why to do Leveling (Heijunka)

- An Introduction to Capacity Leveling

- Theory of Every Part Every Interval (EPEI) Leveling, Also Known as Heijunka

- The Folly of EPEI Leveling in Practice – Part 1

- The Folly of EPEI Leveling in Practice – Part 2

- Introduction to One-Piece Flow Leveling – Part 1 Theory

- Introduction to One-Piece Flow Leveling – Part 2 Implementation

Also, Michel Baudin wrote a post on Theories of Lean and Leveling/Heijunka on his blog with a review of my series on Leveling. Some of his comments helped me to update and improve the above post. Check his post out for further details on Leveling.

Hi Roser,

Happy new year and welcome back ,for one piece leveling I think the changover should minimize to zero then we have capacity to do so ,

Is it right

Thanks and best regards

Hello Felix,

Happy New Year to you, too. You are absolutely correct, if you can reduce the change over time to Zero with a reasonable effort, then you should do so. This will make your planning much easier.

Best regards,

Chris

I’m looking forward to the implementation post. It may answer some of my questions…

I’m struggling to see how a process that cannot maintain EPEI is going to be able to accomplish one piece flow? In my mind one piece flow is just EPEI at the shortest possible interval. If you can’t manage to run every part every day, how are you going to run every part every few hours? My experience is with production managers (myself included) who will avoid changing over at all costs to the point that they will not run parts for up to 2-3 months in order to build up the lot size and make it “economical”. Getting them to run every product every month seems like a good first step and getting them to run every product every week seems like a good goal. You are promoting jumping right ahead to running every product every 8 hours…

The hard part for me to get over is how this will work in practice:

“It is truly what you need to produce today based on the best available data, forecasts, and demands you have today.”

When you have a culture that avoids changeovers at all cost, they are usually in a mode where they are putting off running actual orders that are right in front of them today. They don’t want to run that order because they don’t want to do the changeover (even if it isn’t that big of an overall capacity impact…). In general, they need to produce every part every day because there are real orders for parts every day. Instead they are running every part every month in order to avoid changeovers. This is why I would shoot for a goal of running every part every week instead.

I can see where you are coming from. The idea that the interval repeats perfectly is simple fallacy. I think that the importance in what you are saying is that you need to reschedule every interval. If the interval is going to be daily, then you need to schedule what needs to be run that day every day (instead of counting on today being the same as yesterday). If the interval is going to be weekly, then you need to schedule weekly so that you aren’t effectively trying to predict a schedule a month or more out…

“I’m looking forward to the implementation post. It may answer some of my questions…” Now it does 🙂 (at least I hope)

Hello Kris, and thanks for the longest comment on my blog so far (followed by the longest answer so far).

The problem with EPEI are mostly the long periods that are fixed. With one piece flow leveling you do not fix any longer period than necessary (often e.g. one day). Within that period, you try to mix your production as much as possible to satisfy the demand for that period. There is no need to produce “every part” as per EPEI. Produce only what you need.

Of course, this requires a lot size that allows you to change over multiple times every day (Lot size one would be perfect, but it is not strictly necessary.) However, it sounds like your shop is far from that.

If I would be you, I would focus on reducing lot size, but not care about any particular pattern. In your situation the pattern would not bring much benefit anyway, and would probably harm your production. A smaller lot size, however, would reduce for example your inventory and its cost. If you could change over twice as often, your buffer stock due to change overs would half. This would have a significant cost benefit (see https://www.allaboutlean.com/inventory-cost/. Hence, try to get more frequent change overs, but do not try any pattern!

Hope this helps, let me know if you have more questions.

Cheers,

Chris

Hello Chris,

Thank you for your blog posts which really make me think.

When we are dealing with big machines and the changeovers are not yet on the single-digit minutes target (big metal stamping in my case), the greatest benefit I have seen on our plant in having some kind of pattern is that everyone (production, maintenance, quality, engineering) starts to know by head that those parts/tools will be in production around that day of week, every week in our case. We only try to fix this weekly pattern for our high-runners and let all the other parts fill the remaining slots depending on customer forecasted demand.

To share my experience: The biggest benefit I have seen so far in the pattern is that we reduced lot sizes on high-runners and also a big amount of “planning/coordination” on the support teams, at least for those tools/products. We also tried it on 3 critical machines first, no penalties associated whatsoever… Actually by using the deviations to a pattern as a continuous improvement tool and not a problem in itself seems to work well and the teams really seem to like it. We also didn’t promote this internally as the next “big thing”, and it started as an experiment…

So, I’m not really sure if we are doing a kind of EPEI (not that it matters though) but having some kind of pattern or rhythm (and using this as something that makes problem more visible) seems to help a lot.What do you think?

Thank you,

Pedro Sousa

Hello Pedro,

thanks for your input and compliments 🙂

I am glad the pattern works out for you. Do you have a fixed quantity, or do you just make as much as you need at that time? The latter is more flexible, and less likely to run in problems with stock outs and overproduction due to incorrect predictions. As demonstrated by you, such a pattern can work and give a rhythm to the plant. Not sure if i would call it leveling if the quantity is not fixed, but then, I don’t care too much about the names as long as it works.

As for the deviation as a continuous improvement tool: I wrote these posts, and afterwards during my holidays I got finally around to read Mike Rother “Kata”. Bad timing on my side, should have read this first. Mike also says that an EPEI pattern does not work, and that Toyota uses it to see where they deviate from the pattern for their Kaizen actives. Similar to my recommendation, Toyota ditches the pattern at the first sign of trouble, but then tries to understand why it did not work. Minor difference between Mike and me: Mike recommends this type of Kaizen leveling generally, I believe it is beneficial only if your system already has a basic stability.

Again, thanks for the input, I am always glad to hear from my readers!

Happy New Year,

Chris

I like this discussion.

I always teach heijunka in relation to pull. I think it is important to note that these are two competing concepts. Pull is a system designed to optimize performance of a customer. Heijunka is a system designed to optimize performance of suppliers. Suppliers want perfect predictability and customers want perfect flexibility. For any given operation the choice between optimizing suppliers and optimizing customers has to be made. This is what a value stream map is really supposed to do: determine the pacemaker that will optimize performance for the rest of the value stream by leveling demand.

At the pacemaker, heijunka patterning still makes sense to me. It IS very hard but it is also VERY valuable. When accomplished, it can completely change the dynamics of the entire value stream and reduce inventory caused by buffering immensely. I have seen all of the failures and heartache that you talk about in these articles myself and they are especially bad when heijunka is done without understanding it’s purpose.

I think of EPEI as something different than heijunka patterns however. I think of EPEI more as a metric or health indicator and it doesn’t have anything to do with volume. When I go to a pacemaker operation, I ask them what their current Interval is. I don’t ask them to install Every Part Every Interval. I ask what interval of time currently exists in which they will run every part that there is currently demand for (the interval already exists…). Then we can have a discussion about the impact of the length of that interval on their suppliers. This is most important when different suppliers make components for different parts. When you are running one part, the other supplier is either sitting idle or running to inventory. In those situations particularly, it makes a lot of sense to take on a strategy to decrease the Interval. Instead of running Every Part Every Month, you set the goal to run Every Part Every Week. By doing that, you can cut your inventory needed from a supplier by 75%.

How you accomplish meeting the strategic objective might mean using a heijunka board but it doesn’t necessarily have to. You can use whatever scheduling tool you currently do as long as it can effectively shedule more changeovers in shorter intervals.

Hi Kris,

Good point: Pull for customers, push for suppliers (including internal customers/suppliers). Although both also have big advantages for the production itself, making it easier to organize production.

I strongly believe that only a quite advanced (lean) production system should attempt a EPEI pattern, otherwise there is a lack of stability needed for a pattern to hold. The pattern should also include standards for when and how to deviate from the pattern if necessary. I can imagine a pattern works easier if there is no fixed volume attached to the pattern, with only the sequence of high runner products is fixed.

I agree that EPEI can also be a KPI:How long before you produce these parts again. This is one possibility to measure the responsiveness of the system. Personally, however, i prefer to measure the reach of a lot size, I find this often easier to measure and more difficult to fudge (it is always a risk to get fudged numbers, think OEE or delivery performance 🙁 ) With reliable numbers, however, the understanding of the system should be similar.

Very good discussion, thank you for your input!

Chris

Hello Chris,

We don’t run with a fixed quantity, we actually just build what we need in the amount of time we allocated. If we run into too much problems we use the time of non green items or we just abandon the pattern until we recover.

Happy new year and thank you for this great discussion,

Pedro

Hi Pedro,

your approach without fixed quantity and abandoning the pattern in case of problems sounds like pretty much the only thing that I can imagine that works for patterns. One (possible) suggestion: I would recommend keeping non-green items in the queue and reduce green items if capacity is an issue. You need less green items (high runners) to buffer capacity fluctuations than you would need non-green items. Reducing non-green items is more likely to lead to delivery problems. Of course this all depends on the details of your system.

Best wishes,

Chris

Hi! I don’t know if it is the right place for my question, but I will give it shot!

I studying a course called “Operation management” and there an exercise where you are supposed to calculate the EPE. I know the formula which is: Tsu/Tav-Tpro and in the exercise we two type of products, standard and tailored where the standard has 5 set-ups and the tailored one has 20 set-up/day, How should I calculate Tsu and and Tpro? (How should I take these set ups into consideration?)

Hope you could answer!

Hello Jala,

unfortunately I am not familiar with the Tsu/Tav notation, and am not sure what exactly you need to calculate it. Sorry,

Chris

could you pls explain how to work out heijunka box?thank you

Hi Roser,

good introduction and very useful,but one thing what I interest is how to work out the Heijunka box?could you pls explain detail and one case step by step is better,thank you.