In the previous posts on this series of the Toyota Practical Problem Solving (PPS) I went into detail on how to understand the problem by clarifying the problem and breaking it down to get the prioritized problem. In this post I will look at target setting and root-cause analysis. Setting the target and doing the root-cause analysis is still the “Plan” part of PDCA. Only in my next post with the development of countermeasures do we get to the next step of “Do.”

In the previous posts on this series of the Toyota Practical Problem Solving (PPS) I went into detail on how to understand the problem by clarifying the problem and breaking it down to get the prioritized problem. In this post I will look at target setting and root-cause analysis. Setting the target and doing the root-cause analysis is still the “Plan” part of PDCA. Only in my next post with the development of countermeasures do we get to the next step of “Do.”

A Quick Recap

As listed in my previous post, the Toyota Practical Problem Solving approach consists of the steps listed below.

As listed in my previous post, the Toyota Practical Problem Solving approach consists of the steps listed below.

- Clarify the Problem

- Break Down the Problem

- Set a Target

- Root-Cause Analysis

- Develop Countermeasures and Implement

- Monitor Process and Results

- Standardize and Share

Set a Target

At first glance, setting a target would be easy. We most likely already looked at a deviation of a performance measure from its target during the clarification of the problem. It would be quite easy to take this as a target to get the performance measure back on track. However, don’t do that. The deviation of the performance measure from its target during the clarification of the problem was (intentionally) selected on a high level. If we simply take this target as our improvement target, we are including many secondary effects that may influence the measure.

At first glance, setting a target would be easy. We most likely already looked at a deviation of a performance measure from its target during the clarification of the problem. It would be quite easy to take this as a target to get the performance measure back on track. However, don’t do that. The deviation of the performance measure from its target during the clarification of the problem was (intentionally) selected on a high level. If we simply take this target as our improvement target, we are including many secondary effects that may influence the measure.

For example, if we want to address a problem related to cost, we should not have a cost target. There are so many other factors that influence cost that it would be hard to evaluate the true impact of the improvement.

Instead, we should use the prioritized problem based on our breakdown of the problem. While the initial problem clarification casts a wide net, the prioritized problem should be quite a bit narrowed down. The target should reflect this prioritized problem. For example, if your overall problem is quality complaints, then during the breakdown you analyzed what type of quality complaints, where, when, and who. Setting the target should be very focused on this what—where—when—who analysis.

Just like any other target, it should be SMART, which stands for Specific, Measurable, Appropriate, Reasonable, and Time-Bound. It should answer the three questions What? By when? and How much? for the prioritized problem. As for the magnitude, Toyota calls this “gentle tension.” It should not be too easy, but still obtainable.

Root-Cause Analysis

Once you have your target, you can move to the root-cause analysis (sometimes also called cause and effect analysis). The breakdown of the problem should significantly help you here. The goal is to find the direct cause or causes. This is generally done as a group-effort brainstorming. Keep in mind that, depending on your company’s culture, teamwork can quickly turn into a blame game. Try your best to keep the focus on the problem rather than the person responsible. Try to distinguish between opinions and facts, and avoid generalizations. In case of doubt, go to the shop floor and observe or collect data. This data can then also be stratified like we did during the breakdown of the problem.

Once you have your target, you can move to the root-cause analysis (sometimes also called cause and effect analysis). The breakdown of the problem should significantly help you here. The goal is to find the direct cause or causes. This is generally done as a group-effort brainstorming. Keep in mind that, depending on your company’s culture, teamwork can quickly turn into a blame game. Try your best to keep the focus on the problem rather than the person responsible. Try to distinguish between opinions and facts, and avoid generalizations. In case of doubt, go to the shop floor and observe or collect data. This data can then also be stratified like we did during the breakdown of the problem.

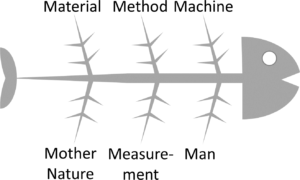

As for the analysis of the root cause, there are a number of different tools there. Toyota often uses a fish-bone diagram (which is kind of a structured mind map). In Japan it is also called Ishikawa diagram, named after Kaoru Ishikawa (石川馨). The head of the fish should be the prioritized problem. The fish-bone diagram can work well even if there are multiple causes.

The different bones can be labeled for example Material, Method, Machine, Measurement, Man (or the gender-neutral member) and Mother Nature (or Milieu, to use a word with M for environment). You can also add Management or Money. If you don’t like “M,” you could also use product/service, price, place, promotion, people/personnel, process, physical evidence; or if you don’t like “P” either, use surroundings, suppliers, systems, skills, safety.

Another problem-solving tool that is particularly useful for more straightforward problems is 5 Why. The basics of 5 Why are rather simple. You just ask the question “Why?” five times to find the root cause of a problem. It works best with problems that probably have only a single root cause, or at least very few root causes. The more possible causes a problem has, the more difficult it will be to use this method.

Another problem-solving tool that is particularly useful for more straightforward problems is 5 Why. The basics of 5 Why are rather simple. You just ask the question “Why?” five times to find the root cause of a problem. It works best with problems that probably have only a single root cause, or at least very few root causes. The more possible causes a problem has, the more difficult it will be to use this method.

After going through 5 Why, there is also a test going back in reverse. This is called the “therefore” test or “So what” test. This is a test to check the validity of the answers. While not foolproof, it may help you to make sure your logical chain is correct. See my blog post All About 5 Why for more.

After going through 5 Why, there is also a test going back in reverse. This is called the “therefore” test or “So what” test. This is a test to check the validity of the answers. While not foolproof, it may help you to make sure your logical chain is correct. See my blog post All About 5 Why for more.

There are many more problem-solving tools and creativity techniques like the 6-3-5 Technique or Fast Networking (see my blog post Fishbone Diagrams and Mind Maps), Creative Provocation, Reverse Brainstorming, Buzzword Lists and Analogy (see my blog post Creative Provocation, Reverse Brainstorming, and Analogy), to name just a few. If you had a positive experience with one of these tools, keep on using them.

Once you have the root cause you can move on to develop countermeasures, and hence finally get to the “Do” part of PDCA (which is so popular that often the entire Plan is skipped… but do not expect sustainable solutions if you skip on the “Plan”). Also, keep in mind that if you have multiple root causes, you may have to develop countermeasures for them separately. But this will be discussed in more detail in my next post. Now, go out, understand the root cause of your prioritized problem, and organize your industry!

PS: Many thanks to the team from the Toyota Lean Management Centre at the Toyota UK Deeside engine plant in Wales, where I participated in their 5-day course. This course gave us a lot of access to the Toyota shop floor, and we spent hours on the shop floor looking at processes. In my view, this the only generally accessible course by Toyota that gives such a level of shop floor involvement.

Can you elaborate on how do you establish Possible Causes avoiding correlation, using Fishbone Diagram

THank you for sharing

Hi Eduardo, the fishbone diagram is merely a structure to help people think and to make it less likely to forget a possible source of problems. The success of the fishbone still depends on the people using it. And, in my experience, there may often be more than one cause, and you may have correlation.

First time I have seen the clarity for Ishikawa vs 5 Why limitations. This is a great callout as they are often mentioned as alternatives – one or the other – almost interchangeable or peer root cause tools, when in actuality Ishikawa is much more robust tool. Kudos!

I suggest for all to re-read Dr Ishikawa’s two books – the first “Guide to QC” explains his “Cause Analysis” (3 types); that he never called Types A and B “Fishbone@; his last book (RIP) presented to me JUSE HQ Tokyo, ‘Introduction to QC”.