The next pillar of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) is Early Equipment management. This includes topics like design for maintenance. It is also a valid tool, although it is hard to estimate how much early equipment management is right for your company. Nevertheless, it may give you inspiration to improve your shop floor.

The next pillar of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) is Early Equipment management. This includes topics like design for maintenance. It is also a valid tool, although it is hard to estimate how much early equipment management is right for your company. Nevertheless, it may give you inspiration to improve your shop floor.

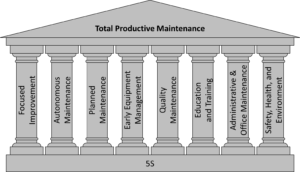

For a quick reference, here again are the eight pillars of TPM. The bold one is the focus of this blog post.

- Focused Improvement (meaning Continuous Improvement)

- Autonomous Maintenance

- Planned Maintenance

- Early Equipment Management (meaning Design for Maintenance)

- Quality Maintenance (which in lean would be called Jidoka)

- Education and Training (which in lean would be part of standardization)

- Administrative & Office Maintenance

- Safety, Health, and Environment

Overview of Early Equipment Management

Early equipment management is about what you can do before maintenance happens. In Japanese this is Shoki Kanri (初期 管理 for early; initial stage and control; management). Early equipment management seems to have different meanings in Total Productive Maintenance. Usually it is called early equipment management (or variants thereof), and focuses on the design of the machine to make maintenance easier. You could call it design for maintenance, although it also includes additional elements. Sometimes it is called start-up monitoring or ramp-up management, and the goal is to have a faster ramp-up after a maintenance. This is sort of a SMED for maintenance. Sometimes it is even dropped completely, and the TPM house has only seven pillars.

To me it is one of the wobblier pillars of TPM, and there are many different opinions on what this pillar actually is. This topic also often drifts off into product design, and general machine efficiency and performance topics, both of which are for me separate topics from maintenance. It may be that TPM is trying to span up an overarching umbrella for all manufacturing topics, and forces the whole efficiency and productivity topics into this pillar. To me this is the wrong approach, and there are other (and better) tools available for this. Hence, in the following I will focus on the actual maintenance aspect of the early equipment management pillar. In any case, it does contain sensible elements.

How to Do Early Equipment Management

Let’s start with the machine design. You can put in effort to design your machine for easy maintenance. Here you try to reduce the duration and labor cost for maintenance. To give you an example, in most cars the battery is easily accessible and replacing the battery is usually not a big task. Since a car battery lasts from four to six years, it may have to be replaced multiple times during the lifespan of a car. However, some cars have their battery in odd and hard-to-access spots. Sometimes you have to remove a wheel to access the battery (which means you have to jack up the car too). In some extreme examples, you even have to take out the complete engine to get to the battery. A 15-minute swap of a battery turned into a 2+ hour highly complex and error-prone task. Clearly, one is easier than the other.

You can also design your machine for inexpensive maintenance. Here you try to reduce the expense on spare parts. Again, take your car as an example. When a headlight failed in older cars, you merely had to replace the light bulb, with material costs being a few dollars. Nowadays, you often have to replace the entire light module, costing you easily hundreds of dollars.

Another possibility is to design your machine for infrequent maintenance. You want to make your machine more reliable, so your maintenance intervals can be longer. With your car, you may buy a long-life oil filter, allowing you to drive longer between oil changes (use at your own risk). Similarly, for your machine this can reduce the frequency of planned maintenance.

Another possibility is to design your machine for infrequent maintenance. You want to make your machine more reliable, so your maintenance intervals can be longer. With your car, you may buy a long-life oil filter, allowing you to drive longer between oil changes (use at your own risk). Similarly, for your machine this can reduce the frequency of planned maintenance.

Closely related is to design your machine for infrequent breakdowns. It may cost more to design and build a higher-quality machine using higher-quality parts, but this results in fewer unplanned breakdowns. When talking with taxi drivers (who obviously drive a lot), they often tell me that a Mercedes transmission lasts for around 100 000 km (60 000 miles). A Toyota transmission lasts in excess of 400 000 km (250 000 miles), which is more than what even taxi drivers drive. Combined with the design for easy and infrequent maintenance the goal is to improve the OEE.

Closely related is to design your machine for infrequent breakdowns. It may cost more to design and build a higher-quality machine using higher-quality parts, but this results in fewer unplanned breakdowns. When talking with taxi drivers (who obviously drive a lot), they often tell me that a Mercedes transmission lasts for around 100 000 km (60 000 miles). A Toyota transmission lasts in excess of 400 000 km (250 000 miles), which is more than what even taxi drivers drive. Combined with the design for easy and infrequent maintenance the goal is to improve the OEE.

Machine breakdowns are bad, but even worse is an injured operator. Hence, design your machine for safety. Here you will find lots of examples in your car. Some are very visible like seat belts or airbags. Others are less visible like designed crumple zones, safety cells, steering wheel retractors, and many more which you will notice only if you crash (and then your mind is probably not focusing on these). It is amazing what kinds of crashes people survive nowadays. Even more crashes are avoided through other safety features like anti-lock braking systems, emergency braking assist systems, electronic stability control (ESC), collision avoidance systems, and many more. A very important topic, although here we start to move away from maintenance and toward general sensible advice regardless of maintenance.

TPM may also include topics like design for quality or design for cost, or the related life-cycle cost. However, while important, these are for me too far removed from maintenance, and I would see them as part of the maintenance organization. Sometimes, training the employees in how to handle and maintain the machine is also included, but this is already part of the education and training pillar, hence to me it is redundant here too. In some sources, the development lead time and concurrent engineering are also included. This is sometimes called early product maintenance. However, this also is for me too far off topic, and is better covered with other methods.

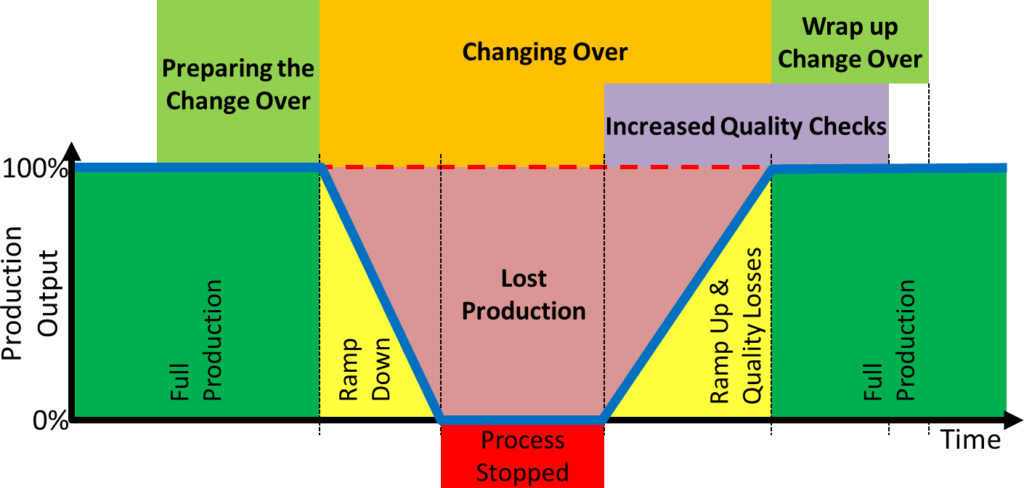

More relevant is the topic of ramp-up management, where sometimes the entire pillar is called ramp-up management. The idea is to go from the end of the maintenance activities to full production as fast as possible. Often this is simply turning on the machine. However, in other cases it may require more readjustment and calibration, leading to slower production and possibly defective parts before the system is up and running again. This again is a valid topic for maintenance. Unfortunately, in my view there are some gaps. You may sometimes also have a ramp-down process. And, if we are aiming to reduce the overall duration, we can also have a look at the maintenance process itself. Luckily, there is already a well-known and useful tool that covers this topic: SMED, also known as quick changeover. While SMED is designed to reduce ramp-down, idle, and ramp-up time for the set-up process, it can be used pretty much identically for reducing the reduce ramp-down, idle, and ramp-up time for the maintenance process.

How Much Early Equipment Management is Good?

Overall, there are lots of things you can do to reduce the maintenance effort and to improve the OEE. The tough question, however, is: Should you? All those possible actions above will have a cost, sometimes more, sometimes less, but usually something you can estimate. They will also have a benefit, which will be much MUCH harder to estimate. Going overboard and doing too much early equipment management may be wasting just as much money as doing too little. But nobody knows what exactly the right amount of early equipment management is.

An additional complication is that there is a significant delay between the cost of doing early equipment management and receiving the benefit of it. An additional complication is that the manager in charge of the machine purchasing & development budget is different from the manager in charge of the maintenance budget. The development manager may need to spend more money, while the maintenance manager reaps the benefit. This may not always happen. Eventually, someone has to make a decision with insufficient data (although this is normal for management). If you have to make a decision, take the best guess of the cost and benefit that you and your people can do. Now, go out, design your machines so they run better, and organize your industry!

P.S.: Many thanks to Leandro Barreda and Gil Santos for nudging me to write about maintenance.

Series Overview

- A Brief History of Maintenance

- What Are the Goals of Maintenance?

- An Overview of the Eight Pillars of Total Productive Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Focused Improvement

- The Pillars of TPM – Autonomous Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Planned Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Early Equipment Management

- The Pillars of TPM – Quality, Training, Administration, and Safety

- The Pillars of TPM – The Missing Pillar Reactive Maintenance?

All good stuff, as usual!

Regarding the cost of Early Equipment Management, EEM

A simple rule of thumb could be

– Not so cost effecient if the machine/line is running in a one- or two shift operation. Overtime can

be used to catch up.

– If the machine is running in a three-shift operation, overtime can only be used during the

weekend. EEM probably is an option.

– In an 24/7 operation, EEM is a “must”

Hi Christoph!

Just wanted to let you know, its not possible to email you through your contact form, something about Google ReCAPTCHA verification faliure, and there is no button available for clicking to verify that “i am human” there is no way to bypass the problem

Great article by the way!

Hi Samuel, thanks for the info. I added a google captcha, but apparently it did not work. Rolled back, next time I will test it before adding. Thanks for the catch!

When designing for maintenance one consideration should be to give the operator opportunity to perform daily maintenance while the machine is running. This can be achieved through items like access to lubrication ports outside of guarding. Eliminating small daily stoppages all add up in machine utilization and product quality