Manufacturing systems have fluctuations. Material may arrive sooner or later. Production may be fast or not. The customer may order more or less. Generally, the less fluctuations you have, the more efficiently you can produce. Toyota puts in an enormous effort to control fluctuation, but even they have fluctuation. In this post I would like to show you the three basic ways how you can decouple fluctuations: inventory, capacity, and time.

Manufacturing systems have fluctuations. Material may arrive sooner or later. Production may be fast or not. The customer may order more or less. Generally, the less fluctuations you have, the more efficiently you can produce. Toyota puts in an enormous effort to control fluctuation, but even they have fluctuation. In this post I would like to show you the three basic ways how you can decouple fluctuations: inventory, capacity, and time.

A Few Sources of Fluctuations

Fluctuations can come from everywhere. Your supplier could be early or late, bring too little or too much, have good quality or not. Customers are also known for random behavior, ordering more, ordering less, canceling an existing order, changing quantities, moving delivery dates forward or back. You also have fluctuations in your own system. Machines may be faster or slower than usual, or may have a breakdown altogether. Your operators may be trained or not, ready to work or sick at home. Supporting processes can also cause changes to the production program if a product is not yet designed yet or the work standards are missing. Overall, there are many sources of fluctuations.

In this post I will focus on fluctuations in the material flow, especially toward the customer. However, keep in mind that there are many other types of fluctuations as well (e.g., within quality or profit).

The Three Ways to Decouple Fluctuations

There are three fundamental ways how you can decouple fluctuations: inventory, capacity, and time. Each of them has different advantages and disadvantages. Depending on your exact situation, a mix of these three may be best for you. Let’s go through this triforce of inventory, capacity, and time.

There are three fundamental ways how you can decouple fluctuations: inventory, capacity, and time. Each of them has different advantages and disadvantages. Depending on your exact situation, a mix of these three may be best for you. Let’s go through this triforce of inventory, capacity, and time.

Inventory

Inventory is probably the first thing most people think of when considering decoupling fluctuations. You just add a buffer stock between your processes. If you temporarily need more than what you can produce, you take parts out of the inventory. If you temporarily produce more than what you need, you increase the buffer stock.

Using inventory is probably the easiest way to have a structured decoupling of fluctuations. You can add it pretty much between every process to buffer the fluctuations between the processes. This makes it also one of the most popular ways to decouple fluctuations.

The downside of inventory is the cost of the inventory. Traditional cost accounting looks primarily at the cost of capital. Unfortunately, this is only a small part of the overall cost. There are many more costs, like insurance, storage cost, handling, administration, obsolescence, defects, deterioration, and increased lead time. Many of them cannot reliably be calculated, hence cost accounting just leaves them out. But they are still there. Overall, you can expect to pay between 30% and 65% of the material value per year just for the privilege of having the material. For more on this, see my post on The Hidden and Not-So-Hidden Costs of Inventory.

The downside of inventory is the cost of the inventory. Traditional cost accounting looks primarily at the cost of capital. Unfortunately, this is only a small part of the overall cost. There are many more costs, like insurance, storage cost, handling, administration, obsolescence, defects, deterioration, and increased lead time. Many of them cannot reliably be calculated, hence cost accounting just leaves them out. But they are still there. Overall, you can expect to pay between 30% and 65% of the material value per year just for the privilege of having the material. For more on this, see my post on The Hidden and Not-So-Hidden Costs of Inventory.

Additionally, inventory can cover fluctuations around the mean demand, but not long-term changes. If your customer continuously wants more than what you can produce, your inventory is going to run out eventually. If your customer continuously orders less than what you produce, your inventory will explode. In the latter case, the great advantage of a pull system is its ability to limit the maximum inventory (see The (True) Difference Between Push and Pull and Why Pull Is So Great! for more details). Overall, inventory alone is rarely the answer to your problem of fluctuations in demand and supply. You also need to adjust capacity.

Capacity

Another way to decouple fluctuation is by adjusting your capacity. If your customer wants more, you just ramp up the working hours and produce more. If the customer wants less, you just send people home and stop the machines.

I guess you can already see the difficulties with this approach. Few operators are willing to be called in on a moment’s notice and sent home a little later – and rightfully so! The problem with adjusting capacity is the delay between the decision to increase or reduce capacity, and the actual increased or reduced capacity. In Europe, flexible companies can set working hours one week in advance, while less flexible companies set working hours one month in advance or more. Sometimes smaller changes on a short notice are possible with the good will of the operators.

If you need larger increases than possible with your workforce, you have to hire more people. However, it will take probably months before you see a noticeable effect. If you need more machines, it may take even longer. To install a new custom made set of machines easily takes 6 months. If you build a new plant, measure the delay in years.

Same if you want to reduce your capacity. If you have to fire your workers, this may take months or even longer depending on your local labor laws. Getting rid of old machines is faster, but used machinery has quite a markdown on price.

Additionally, with inventory you could create a pile of finished goods at one spot at the end of your value chain. With capacity, however, you need to adjust the entire value chain up to the new capacity. If you forget to increase capacity in one process, your entire system will not be able to produce more than the bottleneck process. Please keep in mind that the bottleneck could also be your supplier, which has to make the same move up or down as you do. If you forget to decrease capacity in one process, the problem is smaller, but you still have people or machines waiting for work.

On the plus side, changes in capacity may be cheaper than by increasing inventory. Having your operators work a few hours more per week does not add much to the cost of the product, since most of the labor cost is not fixed but variable cost. In fact, it may make things cheaper since your fixed costs get distributed over more products.

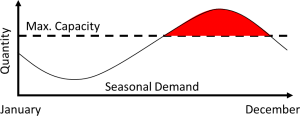

Overall, changes in capacity are slow but economical. Hence, they are best used if there is a known long-term behavior or trend. If your sales increase by 5 percent every year, then you can expect how much capacity you need next year. If your demand shows a seasonal curve, you send people on holiday in the off-season and have them work when you need their time most.

Overall, changes in capacity are slow but economical. Hence, they are best used if there is a known long-term behavior or trend. If your sales increase by 5 percent every year, then you can expect how much capacity you need next year. If your demand shows a seasonal curve, you send people on holiday in the off-season and have them work when you need their time most.

Time

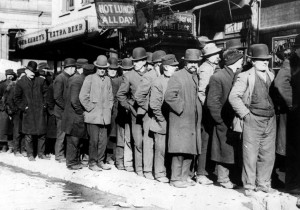

The third way to decouple fluctuations is by time. This is – if you so will – the default option. If you didn’t manage to decouple using buffer or capacity, eventually somebody has to wait. This may be either the customer (if demand is larger than capacity) or your operators and machines (if demand is less than capacity).

Hence, as far as decoupling goes, decoupling through time is the easiest way to decouple, since it happens automatically. Unfortunately, it is often also the least desirable way to decouple. You don’t have to do anything; somebody just has to wait. In fact, many companies that put in an enormous effort to decouple using inventory or capacity still sometimes have to let the customer wait.

The tricky side of the decoupling through time is the cost associated with it. If your operators have to wait, this cost is easy to calculate. Additionally, you can still try to send them home early or use the time to do other things that create value for them. Some companies (e.g., Toyota, Scania) have opted to use the time for improvement activities even if the slump lasts for months (e.g., by sending their operators through training and by improving the processes).

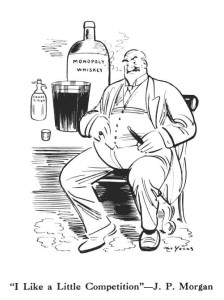

The cost of letting your customer wait, however, is more difficult to assess. If you have a powerful monopoly customer, letting them wait can quickly become expensive. Many automotive manufacturers are not shy about requesting money for line stoppages caused by the supplier, which can quickly reach millions of dollars. If on the other hand you are the monopoly supplier … well … tough luck for the customer. He can’t really go anywhere else. Maybe some of you remember the quality of service and prices of the Bell Systems phone network before the break up of Ma Bell into little bells in 1984? Or the service of the Deutsche Telekom before 1989 (although it seems some of the Deutsche Telekom haven’t noticed yet that they are no longer a monopoly…).

The cost of letting your customer wait, however, is more difficult to assess. If you have a powerful monopoly customer, letting them wait can quickly become expensive. Many automotive manufacturers are not shy about requesting money for line stoppages caused by the supplier, which can quickly reach millions of dollars. If on the other hand you are the monopoly supplier … well … tough luck for the customer. He can’t really go anywhere else. Maybe some of you remember the quality of service and prices of the Bell Systems phone network before the break up of Ma Bell into little bells in 1984? Or the service of the Deutsche Telekom before 1989 (although it seems some of the Deutsche Telekom haven’t noticed yet that they are no longer a monopoly…).

In many cases, these waiting times are used systematically to decouple fluctuations. This is true for companies that sell customized made-to-order products or have market power over their customers. For example, if you order a new Toyota, they will tell you when it fits in their production schedule. Hence, you, the customer, have to wait rather than Toyota stocking up millions of vehicles just in case.

Summary

Most companies use a combination of the above three to decouple fluctuations. Inventory is best used for short-term fluctuations due to its large cost. Slower acting but cheaper capacity is best used to cover larger or longer fluctuations that ideally are predictable. Decoupling through time is the default resort for companies whose market position cannot afford it, and a useful tool for those companies that can afford it.

Of course, do not forget that there are also ways to reduce fluctuation in the first place, as, for example, by working with smaller lot sizes or order sizes (ideally one-piece flow), cooperating with suppliers, etc. (See Introduction to One-Piece Flow Leveling for more.)

How is the situation in your company? Where would you use inventory or capacity, and where could you use time? Think about it when you go out and organize your industry!

1 thought on “The Three Fundamental Ways to Decouple Fluctuations”