This is the second post on different types of pull production. It features the less commonly known approaches of triangle kanban, drum-buffer-rope, reorder point (surprise, yes, it is a pull system), reorder period (also a pull system), and FIFO lanes. In my previous post I showed you the kanban system and its variant, the two-bin system, as well as CONWIP and the kanban-CONWIP hybrid.

This is the second post on different types of pull production. It features the less commonly known approaches of triangle kanban, drum-buffer-rope, reorder point (surprise, yes, it is a pull system), reorder period (also a pull system), and FIFO lanes. In my previous post I showed you the kanban system and its variant, the two-bin system, as well as CONWIP and the kanban-CONWIP hybrid.

Triangle Kanban

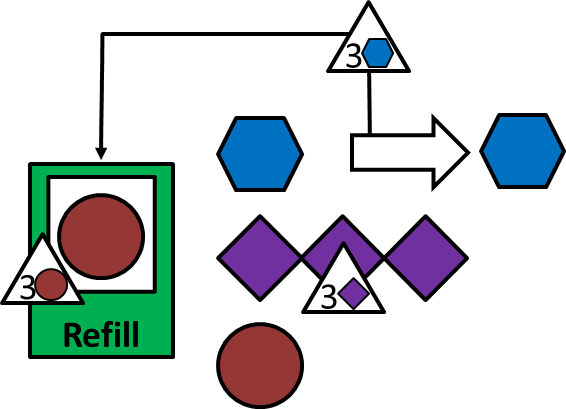

Another variant of the kanban system is the triangle kanban. Instead of every part having a kanban card attached, only the last or second-to-last part in the pile has a kanban card attached. This is called a triangle kanban, since the card at Toyota was initially made from metal scrap and triangular. This triangle kanban gives the signal to reorder or reproduce multiple parts to refill the inventory. When the material arrives, the triangle card is then attached to the last or second-to-last part in the pile, and the process repeats. See Simple Triangle Kanban System for Office Supplies for more.

A triangle kanban will order more parts in larger batches. Rather than one normal kanban per used part (or group of parts), you get one triangle kanban less frequently but with larger quantity. This goes against the basic idea of leveling (small quantities more frequently), but if there is little or no capacity constraint or if the unleveled ordering is not a problem, it can be done to reduce the effort on ordering.

I have seen and used it frequently for office stationary supplies. You don’t send out an order whenever someone takes a blue pen. Instead, when you open the last box of blue pens, you take the triangle kanban and reorder five more boxes of blue pens, which will last you for some time before you have to order again. There is also no problem when you, by coincidence, at the same time order five boxes each of blue, red, green, and black pens, as this “demand peak” won’t overwhelm the capacity of the supplier to deliver.

Drum-Buffer-Rope

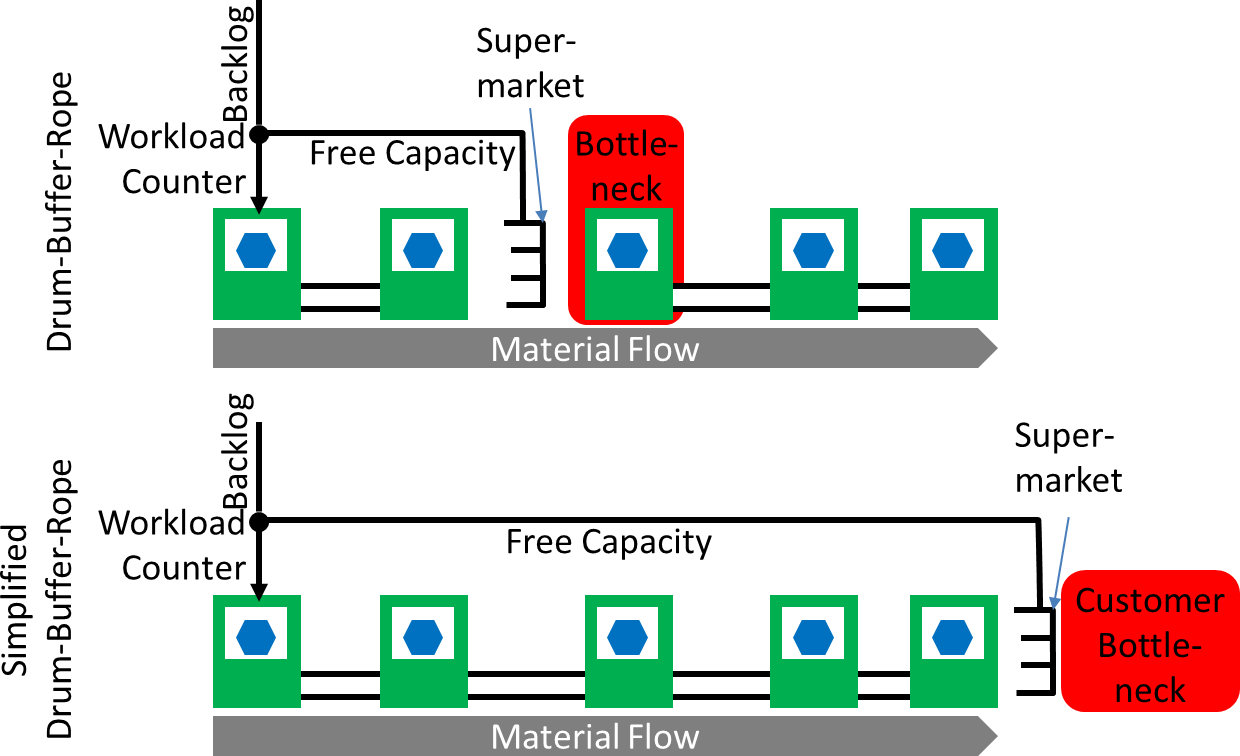

The drum-buffer-rope system was developed by Eliyahu Goldratt. It also is a pull system, but with some limitations. Goldratt is famous for his theory of constraints, and his drum-buffer-rope system is merely an extension to constantly provide the bottleneck with material. Hence he tries to manage the inventory in front of the bottleneck (or for a “simplified drum-buffer-rope system,” the bottleneck is automatically the customer, and the entire line is one big drum-buffer-rope loop).

It is probably most similar to CONWIP. Whenever a part is taken out of the inventory in front of the bottleneck, an information card (similar to a CONWIP card) goes back to the beginning of the line regarding the permission for the production of the next part.

Besides the fixed location of the loop, the second main difference is that he does not count the parts (like kanban or CONWIP), but instead measures the workload. Rather than keeping the number of parts constant, drum-buffer-rope keeps the number of work hours in the system constant. This is beneficial if you have widely different workloads between different jobs (i.e., one order takes 1 hour, another 3 days to complete), but it is more effort. The effort may not be worth the benefit if your jobs are all of similar work content anyway. I wrote more about drum-buffer-rope in A Critical Look at Goldrath’s Drum-Buffer-Rope Method.

While having similar features as CONWIP, it has one in my view major flaw: While managing the inventory in front of the bottleneck has marginal benefits, drum-buffer-rope assumes that the bottleneck does not move over time. However, it does, and frequently so (see About Shifting Bottlenecks). Hence, you have to set up your drum-buffer-rope system under an assumption that is simply not true in most cases.

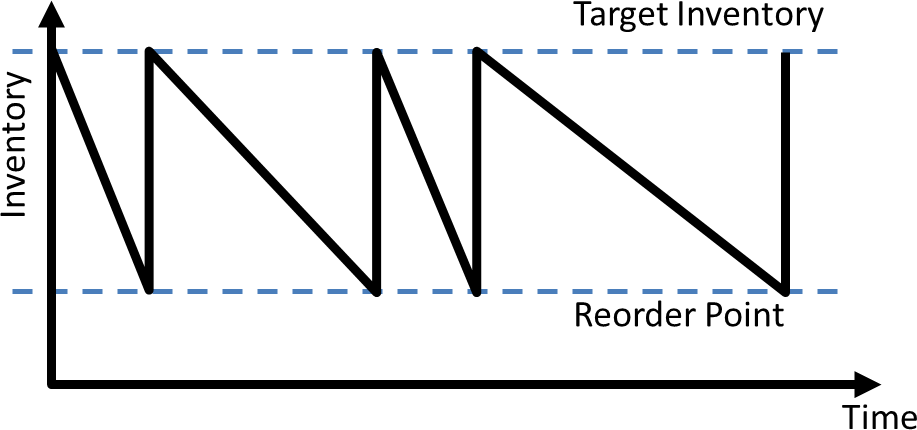

Reorder Point

Yet another way to establish a pull system is a reorder point approach. Okay, now you may be surprised. You may have heard about reorder point before, but never in relation to lean manufacturing. Actually, it is not part of the lean toolset, but its effects make it practically a pull system.

The approach is simple. Whenever your inventory reaches a lower limit (the reorder point), you reorder to fill up the inventory again to the maximum. If your delivery time is zero, you could set the reorder point to zero parts too. However, since in most cases your delivery time is NOT zero, it would be wise to order more parts before you run out. Hence, in practical cases the reorder point is usually not zero.

Please note that the image below is simplified ,as it does not include a reordering delay.

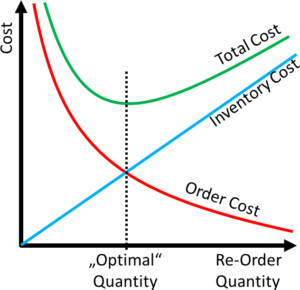

In economics this is often used together with economic order quantity, the quantity to order that supposedly gives you an optimal trade-off between order cost and inventory costs. However, in my experience these calculations usually include numerous assumptions, many of which are not true, and ignore other costs of inventories (see The Hidden and Not-So-Hidden Costs of Inventory). In effect, your supposedly optimal quantity will be too large. I personally avoid this economic order quantity approach and just go with as little inventory as I can get away with without breaking the system.

This system is very similar to a triangle kanban. You have less effort in ordering, but your orders come clumped together, which goes against the idea of leveling. It is doable if your supplier can handle your larger but less frequent orders. But, please note, just because your supplier can handle your order ups and downs doesn’t mean he can do it efficiently. Especially if you are a major customer of your supplier, you may cause your suppliers trouble, therefore you may cause your suppliers expenses, which he will probably forward to you in one way or another.

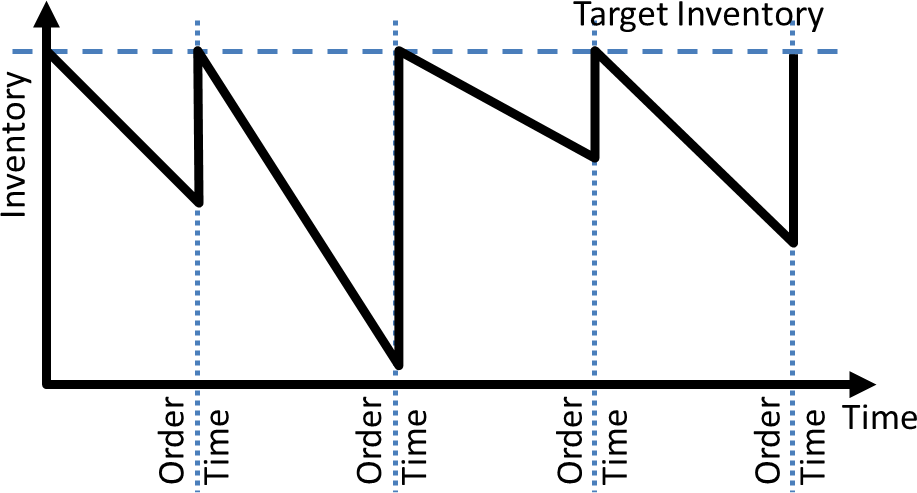

Reorder Periods

Similar to reorder points, it is possible to have reorder periods. With reorder points, you filled up your inventory to the upper limit when you reached a lower limit. With reorder periods, you do this every fixed time interval (e.g., every Friday you order to fill up your inventory). This makes ordering easier and more regular, but requires higher quantities of inventory to avoid a stock out. Otherwise it has the same disadvantages as the reorder point of clumping together your orders and going against the idea of leveling. Please note that the image below is simplified as it does not include a reordering delay.

FIFO

Yet another way to establish a rudimentary pull system is a FIFO lane. By default, a FIFO lane has an upper limit on the number of parts in the system, and hence it is a very rudimentary pull system.

Yet another way to establish a rudimentary pull system is a FIFO lane. By default, a FIFO lane has an upper limit on the number of parts in the system, and hence it is a very rudimentary pull system.

However, it does need a system that supplies the first process with information on what to produce. Therefore, a FIFO on its own would work only if the system produces only one part type, and even then it is usually embedded in a larger system like kanban or CONWIP. Yet, within a larger control system it is an excellent way to even out the distribution of material between processes and to avoid getting a large pile of material in front of one bottleneck process. See Theory and Practice on FiFo Lanes – How Does FiFo Work in Lean Manufacturing? for more.

Others

In (academic) literature, you can find many more options for pull systems. And it is probably easy to come up with alternatives. For example, take the CONWIP system, but do not count jobs and instead measure the workload, as in a drum-buffer-rope system. Voila, your very own CONWIP-drum-buffer-rope hybrid. It will work, although I find the improvement marginal.

I am sure there are other methods out there that I have not yet heard of. Some of them may even work, but many others are academic ivory tower products and probably lacking practicality. I occasionally read about mixed pull-push systems, but I don’t believe that. If you have the benefits of a pull system (i.e., limited inventory), you destroy it again if you introduce push-products. If some products do not have a limited inventory, then it is push for all, not pull. In any case, if I missed a pull system that you think works, let me know!

So, these eight systems are all I know to implement pull production. Surely, there must be one that works for you. Now, go out, implement the pull system of your choice (since pull is really, really, good!), and organize your industry!

Thanks Chris,

one question what kinds inventory and situation we can use Reorder Point or Reorder Periods

what is major difference and impact

thanks

Hi Felix,

Reorder Point and Period are very similar. R-Point allows slightly lower inventories. These stock management systems date from before Toyota’s Kanban system. Their main disadvantage is ordering in larger quantities. If that is OK with you, then you can use them.

Cheers,

Chris

“When the material arrives, the triangle card is then attached to the last or second-to-last part in the pile, and the process repeats.”

At Toyota, the Triangle Kanban links batch building in Stamping to one-piece flow in Body Weld. It schedules Stamping production. Thus, it’s far more complicated than your statement suggests.

“A triangle kanban will order more parts in larger batches. Rather than one normal kanban per used part (or group of parts), you get one triangle kanban less frequently but with larger quantity. This goes against the basic idea of leveling (small quantities more frequently), but if there is little or no capacity constraint or if the unleveled ordering is not a problem, it can be done to reduce the effort on ordering.”

The calculations used in the Triangle set-up serve to maximize changeovers and minimize lot sizes. This actually fulfills the “basic idea of leveling” as it pertains to batch building. This is the goal.

The Triangle is a little known/understood but a critically important part of the Just-In-Time system at Toyota.

Hi Phil, good (and interesting) comment. I have to admit that I did not use Triangle kanbans at Toyota. I have seen it most often in the reorder of office supply, where the order size was mainly determined by the hassle of ordering. However, as you describe a batch to one piece transition, it makes total sense to minimize the triangle quantity to the smallest one you can get away with (i.e. to maximize changeovers). Very good input, thanks for commenting!

This is very good. Thanks Sir Christoph.

I have a question & your answer will help me a lot..

How are JIT & Pull systems different? Can you explain this to me with an example?

I’ll be very grateful. Thanks!

Hi Ankur, Pull is an upper limit on the material in the system. JIT is when the material arrives at the place where it is used. You can combine pull with JIT, although it is easier to start with Pull and later add JIT, since it is more difficult. I have posts on both topics in my list of posts.

Hi Christoph and thanks for great posts!

I recently made an acquaintance with a POLCA-System. Could you please share your ideas and opinion about that? It would be great!

Thanks

Slava