Pull production is one of the most important aspects of lean production. Its key feature is to have an upper limit on inventory that is not to be exceeded. The most well-known way to implement a pull system is by using kanban cards. However, there are many others. In this short series of two posts, I want to give you an overview of the different ways to implement pull systems, and discuss the pros and cons of them.

Pull production is one of the most important aspects of lean production. Its key feature is to have an upper limit on inventory that is not to be exceeded. The most well-known way to implement a pull system is by using kanban cards. However, there are many others. In this short series of two posts, I want to give you an overview of the different ways to implement pull systems, and discuss the pros and cons of them.

Key Feature: Limit the Inventory!

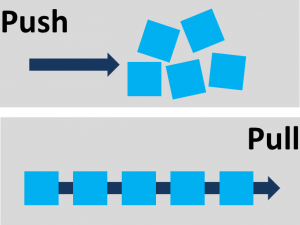

Often, there is confusion on what makes a pull system a pull system. Many believe that a “signal” comes directly from the customer – but that is a pretty fuzzy and flawed definition. Instead, the key feature of a pull system is an upper limit on inventory! I wrote a whole blog post on this: The (True) Difference Between Push and Pull.

This key feature is also its advantage. If set up correctly, pull systems keep the system at the sweet spot with respect to inventory. It does not exceed the upper limit, but it should also not fall too low and cause a lack of material. Best of all, this does not require manual intervention, but should be automatically based on the rules of the pull system.

You can set an upper limit on inventory for every part separately, or for all parts combined. If you do this for every part separately, the system also automatically manages the production plan (if you take out one part, reproduce exactly this part type). Examples would be kanban, triangle kanban, two bin systems, and reorder points or reorder periods. If you set an upper limit for all parts regardless of the part number, you do need to have a system in place that defines which parts to produce next once you fall below this limit. Examples would be CONWIP systems, drum-buffer-rope, or FIFO lanes. These combined upper limit , on the other hand, has the advantage of lower fluctuations in the total workload, whereas a limit-by-part-number approach can fluctuate more.

Where You Can Do Pull, and Where You Cannot

This makes pull systems overall very robust and stable, well suited for pretty much any production system. In fact, it can also be used outside normal industry (e.g., in healthcare, military, or data processing) (see also my post on Why Pull Is So Great!). There is, however, one requirement for it to work: You need to be able to control the number of new parts or tasks arriving!

This is usually the case in manufacturing. Parts arrive only when you explicitly order or produce them. Without a purchase or production order, you wont get any parts. Thus you can limit the maximum inventory simply by not ordering or producing more when you reach that limit.

However, not all systems have that ability. For example, if you work in retail, the customer comes whenever the customer damn well pleases! It is not practical to send customers away during the Christmas crazy shopping period just so you can limit your number of customers. I mean, of course you can, but it is usually not good business practice. If you cannot control your arrivals, then you have to be much more flexible with your capacity in handling these arrivals (see Lean Tales in Japan: The Japanese Supermarket Checkout for an example).

In any case, as long as you have control over the parts or tasks arriving, you can establish a pull system. There are different ways to do that.

Kanban

This is the most well-known approach to pull. All material in the kanban loop has a kanban attached. This kanban is used for that part type and that part type only. This kanban can be a simple card, a labeled box, or even a wireless RFID chip. Finished material is stored in a supermarket. Whenever a part is removed from the supermarket, the kanban goes back to the beginning of the loop for reproduction (if a kanban stands for more than one part, usually the kanban is returned when the first part is removed). Hence, the kanban card signals production (or generally delivery) of new parts. You can never have more material than indicated on all kanban cards.

This is the most well-known approach to pull. All material in the kanban loop has a kanban attached. This kanban is used for that part type and that part type only. This kanban can be a simple card, a labeled box, or even a wireless RFID chip. Finished material is stored in a supermarket. Whenever a part is removed from the supermarket, the kanban goes back to the beginning of the loop for reproduction (if a kanban stands for more than one part, usually the kanban is returned when the first part is removed). Hence, the kanban card signals production (or generally delivery) of new parts. You can never have more material than indicated on all kanban cards.

A kanban system requires all kanbanized products to be available in stock, and hence this system is usually good for high-volume, low-mix production. However, it won’t work for made-to-order production, and in general is not so good for low-volume, high-mix production.

Two-Bin System

A variant of the kanban system is the two-bin system, sometimes also called two-box system. You have two kanban, often storage bins, hence the name two-bin system. Whenever a bin is empty, the bin is returned to be refilled. This is effectively a kanban system with two cards (bins).

This is used for parts where the replenishment time of a bin is much shorter than the time to empty a bin (i.e., the system can produce or order faster than the customer can consume). You need at least two kanban, otherwise you risk running out of parts if the single bin happens to be empty when you need the part. This can be avoided with two bins.

CONWIP

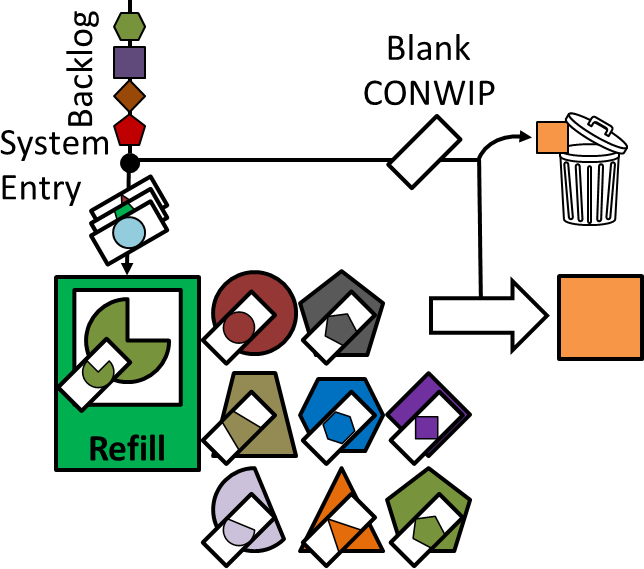

CONWIP stands for “constant work in progress.” It is somewhat similar to kanban, but the CONWIP cards do not represent a specific part. Whenever a kanban comes back for replenishment, it needs to replenish exactly the part on the kanban and no other. When a part is removed from the CONWIP inventory, the CONWIP card is “blanked” (i.e., any part related information is removed). Hence, when a CONWIP card comes back, it merely has the information to produce whatever job is next in line. Therefore, a CONWIP system also needs a backlog list of open jobs to be completed, ideally arranged by priority. Whenever a free CONWIP card comes, the next job in the backlog merges with the card and enters the system.

The advantage of the CONWIP system is that it can be used for low-volume, high-mix products. Hence, it is a system that is commonly used for made-to-order parts. It is possible but somewhat cumbersome to use it for high-volume, low-mix, as the backlog management becomes more complex. Hence, for made-to-stock products it is inferior to kanban. Luckily, kanban and CONWIP can be combined.

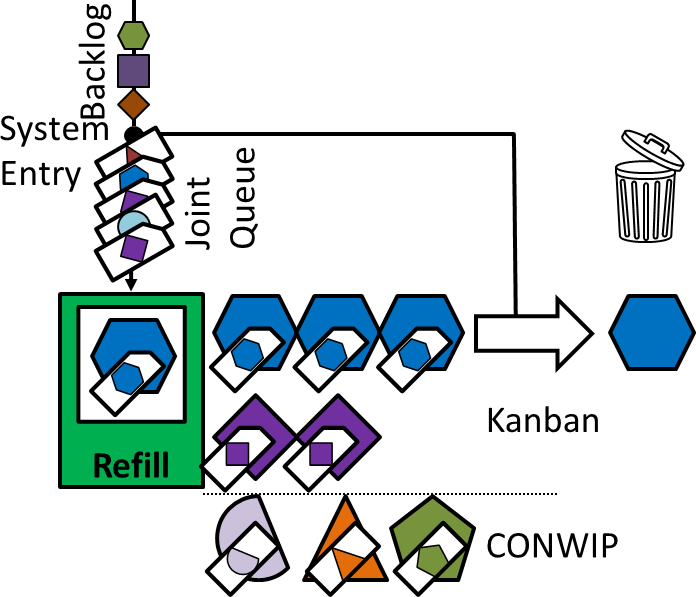

Kanban-CONWIP Mix

Due to its similarities, a kanban and a CONWIP system can easily be combined. You just have to take care on how to merge the kanban and CONWIP cards. There are different options. The easiest one is simply to have a joint queue (see Benefits and Flaws of CONWIP in Comparison to Kanban for more). However, you can also use a priority system. If you have less than 30% of the total workload as CONWIP, I recommend using a priority CONWIP lane, and, only if the CONWIP is empty, taking cards from the second-priority kanban lane. See my series on How to Prioritize Your Work Orders for more on prioritization.

The obvious advantage of such a hybrid system is that it can handle both high-volume, low-mix (the kanban part) and low-volume, high-mix (the CONWIP part) – in other words, both made-to-stock and made-to-order parts.

In my next post I will discuss a few more, namely the triangle kanban, drum-buffer-rope, reorder point (surprise, yes, it is a pull system), reorder period (also a pull system), and FIFO lanes. Until then, stay tuned. Now, go out and organize your industry!

Hi Christoph, Are you aware that pull can now be implemented across complex, even global, enterprise(s) from ‘end to end’ using software instead of VM? (VM is a bit clunky across dispersed networks). Demand Driven MRP is what its called and is composed of 5 key activites – decoupled inventory positioning, their sizing, their maintenance, their consumption based replenishment according to ROP or ROC and flow monitoring (ie. onhand buffer penetration checking). Even SAP have recognised the need and are enabling it with their new releases.

Best regards

Simon

Hi Simon, the above merely explains the structure of how to do pull systems. If it is a paper kanban, a box with a label, or a digital kanban implementation (and similar for CONWIP and others) makes not too much difference. I am always very skeptical about software packages if I don’t understand what they do in the background. The solutions above have to be tailored to your business situation, and if the software gives me an “ones size fits all” solution, it will be an “one size fits none”.

No worries on that Christoph, the buffer sizing in these systems is based on a user selected average (from forecast, history, blend and selected period) for lead-time and cycle interval and service level calculated variability buffer. As you say, the method is very simple and so are the calculations – no black box.

Hi Christoph, indeed a well explained article. Pull system, in my view, is a perfectly balanced Replenishment System/ program. E.g. Just consider a water tank with an overflow outlet at a fixed height and also having a drain at the bottom with a varying outflow.

Depending upon the demand rate, the tank will start draining the water and hence will have to be replenished at this rate to ensure that the tank does not become empty, which indicates dry inventerisation. At the same time, if the incoming water rate is higher than the demand consumption, the take will start overflowing, representing an excessive inventeriasation.

Hi Devendra, the system you described is basically a toilet tank, which always refills to the max but not higher. Unconventional but good example of a pull system.

Mr Eagle, a manufacturing software such as ERP will never replace Visual Management for two main reasons:

1. in order to work, a software makes the premise that the inventory is 100% accurate which is false; and

2. Visual Management allows people to react when something goes wrong.

In other word, the flexibility of a Visual Management system as yet to be seen in any manufacturing software.

Dominic, Christoph, Please see my article re use of pull and software below. We really aren’t talking black box here and now that ERP/SaaS can support a multiple decoupled pull supply chain across global / complex networks I think we’ll see Lean getting a new lease of life.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/taking-lean-c21st-demand-driven-mrp-simon-eagle/?trackingId=UEZ9FAHyVkGHa1tgPyjNyw%3D%3D

Hi Chirstoph,

I’ve recently implemented pull within my plant and it’s been very successful and working as expected. We would like to start expanding to replenish our finished goods (i.e. step before the customer) but we have multiple warehouses/distribution hubs and three factories supplying to the entire market. Are you familiar with other companies who have successful implemented end to end pull with a complex supply chain? I’d love to benchmark with others. Regards.

Hi Amber, Toyota is always a good example for pull systems. So are retail supermarkets. For make to stock your warehouses/hubs should have a target level, and you merely fill up the inventory as it is consumed.

Congrats on implementing pull, by the way. Glad it is working and you are seeing results. Keep on going with the improvement and the PDCA!

I understand the value of VM for inventory and I have used this during my career for many applications from buy parts to sub assembly to finished goods. I also understand that inventories are a headache to some organizations using ERP/MRP and in fact just had this discussion with my partner this week. That said, I believe you must do both. Easy for people on the floor to reorder “visual” but for yield, COGS, scrap, costing, etc. it’s imperative you have the information somewhere. I think the best solution is to incorporate both and hold team accountable to the processes to support both ends of the business.