Most of our prosperity and wealth is based on our ability to manufacture faster, better, and cheaper than ever before. To announce the publication of my first book “Faster, Better, Cheaper” in the History of Manufacturing: From the Stone Age to Lean Manufacturing and Beyond, I would like to start a four post series where I explore this story and tell you a brief version of the History of Manufacturing. In this first post I would like to talk about prehistory, division of labor, mechanization, and manufacturing during antiquity.

Most of our prosperity and wealth is based on our ability to manufacture faster, better, and cheaper than ever before. To announce the publication of my first book “Faster, Better, Cheaper” in the History of Manufacturing: From the Stone Age to Lean Manufacturing and Beyond, I would like to start a four post series where I explore this story and tell you a brief version of the History of Manufacturing. In this first post I would like to talk about prehistory, division of labor, mechanization, and manufacturing during antiquity.

This series is actually a transcript of my first lecture, a German academic tradition where a new professor after a year or so gives a public lecture on a topic of his choice. The video of the entire lecture (in German with Subtitles) is available on YouTube.

Prelude

Ladies and gentlemen, we live in an age of unprecedented prosperity. No generation before ours has had as many material goods as we have. That is thanks in large part to production. The story I would like to tell here is how production developed over thousands and millions of years.

One small part of this is: How can you produce something?

That is just a small part. That is more the history of technology: How can I do something? Much more importantly for production: How can I do it faster? How can I do it better? And most important, how can I do it cheaper?

Therefore, through production becoming faster, better, cheaper, we have achieved a large part of the prosperity that we enjoy today. However, let us start from the beginning.

The Six Manufacturing Techniques – DIN8580

Let us go back two and a half million years, to the first production. In this case the production of stone hand axes in the Stone Age. Homo habilis produced these. They were also the very first representation of the genus Homo, to which we also belong as Homo sapiens. It is no coincidence that habilis comes from Latin, meaning toolmaker or handyman.

Let us go back two and a half million years, to the first production. In this case the production of stone hand axes in the Stone Age. Homo habilis produced these. They were also the very first representation of the genus Homo, to which we also belong as Homo sapiens. It is no coincidence that habilis comes from Latin, meaning toolmaker or handyman.

Homo habilis was the first who really engaged in production. Now we know very little about production at that time, but we have learned a couple of things. For example, the longest-producing manufacturing site in the world is a place in Africa, at which stones were processed for about a million years.

The manufacturing site was between two mountains. Ten kilometers in one direction was one mountain, and ten kilometers in the other direction was the other mountain. We have also learned that there was one corner where new hand axes were produced. The pieces at that location are consistent with stones that were manufactured into new hand axes. Nearby, old hand axes were re-sharpened. The pieces at this site are consistent with the splinters of used hand axes that were reworked and refurbished.

You may of course ask the question, why were the new hand axes in one location but the used ones in another? The logical conclusion would be, they already had the first division of labor. It is not certain, but it is probable that some had already specialized in making new hand axes. Others specialized in reworking old hand axes. Finally, others who were not so skilled with their hands specialized in getting stones from ten kilometers away and bringing them back to the site.

That is already the first evidence of the division of labor. The division of labor makes it possible for us to learn faster. We learned faster how to do something. Through that we became faster, better, and – okay, in the Stone Age it was not so relevant – but … altogether cheaper too. That means that through the division of labor, we had already optimized production in the Stone Age.

We usually divide manufacturing methods into six groups. Producing stone tools was the first technique: cutting.

The second technique was changing material properties, 120,000 years ago. What you see here is the tip of a spear. Wooden spears already existed long before, but this spear tip is hardened. When you put wood into a fire, it burns. However, when you place wood carefully into a fire, turn it, and do not leave it in too long, then the water and moisture evaporate, and the spear becomes harder. That means that already 120,000 years ago, the manufacturing technique of “changing material properties” existed. [Side note: Since the presentation I learned that there is even an older technique that treated stone with heat for better stone tools.]

The second technique was changing material properties, 120,000 years ago. What you see here is the tip of a spear. Wooden spears already existed long before, but this spear tip is hardened. When you put wood into a fire, it burns. However, when you place wood carefully into a fire, turn it, and do not leave it in too long, then the water and moisture evaporate, and the spear becomes harder. That means that already 120,000 years ago, the manufacturing technique of “changing material properties” existed. [Side note: Since the presentation I learned that there is even an older technique that treated stone with heat for better stone tools.]

The next technique was joining, 72,000 years ago. At that time, arrowheads were attached to the wooden arrow shaft with resin and other materials. They made one part out of two and joined the parts together.

The next technique was joining, 72,000 years ago. At that time, arrowheads were attached to the wooden arrow shaft with resin and other materials. They made one part out of two and joined the parts together.

Coating has existed for about 30,000 years, for example in the form of cave paintings. Molding has existed for 25,000 years. The figure was formed from bone dust and clay, and then burned.

Forming has also existed for almost 10,000 years. For forming, we typically need metal. Metal is a malleable material. Already 10,000 years ago, small beads and pendants were formed from metal.

Forming has also existed for almost 10,000 years. For forming, we typically need metal. Metal is a malleable material. Already 10,000 years ago, small beads and pendants were formed from metal.

If you are a little bit familiar with history, you’d say, “Wait a minute! For metal, we definitely need metalworking, and that is from the Bronze Age. But that hadn’t even started yet ten thousand years ago!”

Correct. The metal is a so-called native metal that comes in a pure form in nature. Not often, but occasionally, there’s a piece of copper found in nature. They hammered on these pieces. Before they knew how to liquefy or extract it, they struck it and formed things that way.

Hence, all of the six manufacturing techniques that we know of were applied in one form or another during the Stone Age. Of course, significant technological progress has happened since then.

Division of Labor in Ancient Times

Let us go a couple of million years ahead into ancient times. In the Stone Age, we can only guess at the existence of the division of labor. However, in ancient times, we have written reports. For example, the Greek philosopher and politician Xenophon already observed the division of labor.

In a small city the same man has to build beds, chairs, ploughs and tables and often even to build houses. […] But in the big cities [an artisan will get] his living merely by stitching shoes, another by cutting them out, a third by shaping the upper leathers, and a fourth will do nothing but fit the parts together

He determined that in a small city, craftsmen must actually do everything that even remotely comes under their general area of knowledge.

In a large city, however, they specialized. An example from shoemaking: One worker specialized in sewing the shoe soles; another cut the leather; the third did nothing but place the leather upper, and the fourth did nothing but put the final pieces all together. That means that at that time there was also a relatively good division of labor. As mentioned before, the division of labor makes production faster, better, and cheaper.

Mechanization and Energy Sources

There were also the first machines in ancient Egypt. Thousands of years ago, the pottery wheel already existed. The Egyptians also had the first lathes, at that time of course operated by hand. On the right, you can see a man who is operating the lathe with two cords, and on the left, a man who is holding the instrument in place and ultimately turns it.

There were also the first machines in ancient Egypt. Thousands of years ago, the pottery wheel already existed. The Egyptians also had the first lathes, at that time of course operated by hand. On the right, you can see a man who is operating the lathe with two cords, and on the left, a man who is holding the instrument in place and ultimately turns it.

We human beings are – in terms of living things – very skilled. However, we have no power. Compared to us, animals such as horses have considerably more power than we do. In that respect, it was of course logical that we came up with additional sources of power. For example, the Romans made use of horses and cows relatively early on. Here we have a picture of a Roman flourmill, in which a mule walks in a circle and turns the mill.

We human beings are – in terms of living things – very skilled. However, we have no power. Compared to us, animals such as horses have considerably more power than we do. In that respect, it was of course logical that we came up with additional sources of power. For example, the Romans made use of horses and cows relatively early on. Here we have a picture of a Roman flourmill, in which a mule walks in a circle and turns the mill.

Natural energy sources were also used early on. Here we have a picture of a Persian windmill utilizing wind power. This of course does not look like a Dutch windmill. The wind blows through the middle, and the shaft is vertical, rotating a millstone at the bottom. At that time, they did not yet know how to convert a vertical rotation into a horizontal rotation by using gears.

Natural energy sources were also used early on. Here we have a picture of a Persian windmill utilizing wind power. This of course does not look like a Dutch windmill. The wind blows through the middle, and the shaft is vertical, rotating a millstone at the bottom. At that time, they did not yet know how to convert a vertical rotation into a horizontal rotation by using gears.

It was a similar story with waterpower. The next picture shows a Chinese water mill. You can see how the water flows through underneath and the millstone is on top. Again, for the lack of gear technology, there is just one axle.

It was a similar story with waterpower. The next picture shows a Chinese water mill. You can see how the water flows through underneath and the millstone is on top. Again, for the lack of gear technology, there is just one axle.

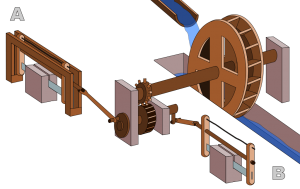

Finally, the Greeks and Romans developed gears. The Romans were also the first to transform a rotation into a back-and-forth movement. Here is an example of a Roman sawmill, where through waterpower a saw is moved back and forth.

Finally, the Greeks and Romans developed gears. The Romans were also the first to transform a rotation into a back-and-forth movement. Here is an example of a Roman sawmill, where through waterpower a saw is moved back and forth.

The Romans were also well known for their agriculture. They bred animals and plants at a never-before-seen level of productivity. Only in the modern era were we again able to reach that level of cultivation of such an animal size and productivity.

Prestige of Craftsmanship in Antiquity

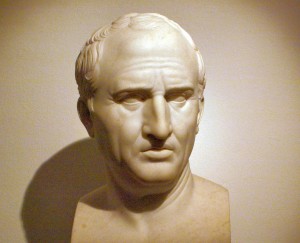

Had the Romans done the same with production, who knows? Maybe we would have already had the Industrial Revolution a thousand years ago. This raises the question: Where would we be now if we would have already had the steam engine a thousand years ago? Unfortunately for the Romans, that was not the case. As for the reason, I will leave that to the best-known Roman orator, Marcus Tullius Cicero, to explain.

Unbecoming to a gentleman, too, and vulgar are the means of livelihood of all hired workmen whom we pay for mere manual labour, not for artistic skill; for in their case the very wage they receive is a pledge of their slavery. [...] And all mechanics are engaged in vulgar trades; for no workshop can have anything liberal about it. “All mechanics are engaged in vulgar trades, for no workshop can have anything liberal about it.” I repeat, “No workshop can have anything liberal about it!”

Most of you earn your money through a craft related to production or manufacturing. In ancient Rome, you would not have been popular. You would not have been invited to any parties. Also, on the marriage market, you would have to settle for the leftovers. The Romans had a very clear opinion of craftsmanship: it was vulgar! Similar for the Chinese, trades and commerce together were not reputable.

Subsequently, “young potentials” would not have gone into manufacturing. You would have gone into politics, agriculture, or the military, but not into manufacturing. Because of that, not much got accomplished in manufacturing. This started to change only in the Middle Ages, as I will show in my next post.

In this series of post I only give a rough overview of the history of manufacturing. If you would like to read more about this history, then check out my book on the history of manufacturing:

In this series of post I only give a rough overview of the history of manufacturing. If you would like to read more about this history, then check out my book on the history of manufacturing:

Roser, Christoph, 2016. “Faster, Better, Cheaper” in the History of Manufacturing: From the Stone Age to Lean Manufacturing and Beyond, 439 pages, 1st ed. Productivity Press.

Now go out, learn the lessons of history, and organize your industry!

Good historical perspective of Manufacturing!

Your discussion of antiquity is centered on process technology. I would very much like to know how production was organized. Unfortunately, there is next to no information available about this.

I would think Rome would deserve a more extensive treatment. Which work of Cicero does your quote come from? I don’t understand the meaning of “no workshop can have anything liberal about it.” What does “liberal” mean in this context?

Did no other Roman author have anything to say on the subject? Like Livy, Tacitus, Suetonius, Lucretius, Marcus Aurelius, …?

Why quote only Cicero? He died in 43BCE, together with the Roman republic. The empire had 500 years ahead of it in the West, and 1,500 in the East. During much of that time, it maintained standing armies in the hundreds of thousands of soldiers and built many structures that still stand.

It must have had some form of military-industrial complex putting out uniforms, body armor, helmets, swords, shields, bows, arrows, carriages, catapults, galleys, etc. and a logistics organization to distribute all this equipment from Britain to the Persian border.

In Hollywood’s swords-and-sandals movies, the legionnaires’ uniforms look as identical as if they have been made today. Only in Gladiator do they look hand-made and worn out. Who were the suppliers? Was there a weapons industry center somewhere in the Empire, or was production capacity available near all the forts and outposts?

Again, I have no information about this whatsoever, and I don’t know whether any records of this activity survived.

Hi Michel, besides the problem of fitting 2.5 million years in 2000 words, there is indeed frightfully little on ancient manufacturing organization that we know. The Cicero quote is from “De Officiis, Boox 1, section 150”, translated by Walter Miller 1913. In his 1913-speak “liberal” probably meant “of or befitting a man of free birth”. I picked Cicero, since it is representative of the feeling in ancient Rome that manufacturing is … yuck! Manufacturing was left to slaves and the bottom of the social hierarchy. There are some treaties on technical issues by others, but most writers didn’t bother with the vulgar manufacturing. Most of what we know is from archaeological records, and few archaeologists have an eye for manufacturing organization.

As for the armies, we don’t even know if they were equipped by the state, by the individual commanders (like the French Army until the French Revolution), or if everybody was supposed to bring their own gear. The Equites (cavalry) definitely had to provide their own horse (and hence presumably the saddle, too). Sea transport was easy, but land transport was prohibitively expensive. It was probably easier to produce weapons locally in Gaul than to bring it from Rome. For mass production I would rather look for amphorae’s, bricks, or oil lamps. We know for example that a famous brand of oil lamps (Fortis) was manufactured on different sites in Europe and Africa, but besides Modena these were probably product pirates using the famous name for their own profit. We don’t know if there was an assembly line production or individual craftsmen (more likely). In food processing there were larger “factories”. E.g. in some bakeries like in Ostia a “production line” material flow from milling to kneading to baking is visible. Similar for fish salting or olive oil pressing. There is of course more in my book. Cheers, Chris.

More on the translation. “no workshop can have anything liberal about it.” in original Latin is “nec enim quicquam ingenuum habere potest officina“. “ingenuum” here means “noble, generous, frank”. The “quicquam ingenuum” can mean “refined”, and “enim quicquam ingenuum” is “For any gentleman”. The absence of either is vulgar 😉 .

Amazing Information

Thanks for giving us an education on ancient history

Thank you

Good information about ancient history

Thank you….

Very informative

it’s really very interesting and information.

Thank you.

Knowledgeable information very good to know that

Good to know information

Amazing Information

Amazing Information

Good Information

Amazing information.it is helpful to grow your historical knowledge in it.

Very informative! Thank you.

Had great training session