Pretty much all companies are based on a hierarchical structure. One superior manages multiple subordinates. The question is: How many subordinates should be managed by a superior? This is also called the span of control. This depends on a number of factors. Let’s have a look at efficient group sizing.

Pretty much all companies are based on a hierarchical structure. One superior manages multiple subordinates. The question is: How many subordinates should be managed by a superior? This is also called the span of control. This depends on a number of factors. Let’s have a look at efficient group sizing.

Introduction

The leadership span depends in short on the workload of the supervisor. If it is a lot of work to supervise, then the supervisor can manage fewer people than if it would be an easy supervision job. This workload of managing people has to be combined with “other” work the supervisor has.

The leadership span depends in short on the workload of the supervisor. If it is a lot of work to supervise, then the supervisor can manage fewer people than if it would be an easy supervision job. This workload of managing people has to be combined with “other” work the supervisor has.

In the end, the time needed to both manage and do other jobs should be sufficient to do all tasks properly. Overloading the supervisor will have him out of necessity doing jobs sloppier or not at all to manage the workload within the available time. If the supervisor has too much work, it may be necessary to adjust the workload by adding hierarchical levels, changing group size, or assisting him with his other tasks.

When determining the right workload, unfortunately, looking at the available free time of the supervisor is not a good indicator. Humans (including supervisors) have the tendency to fill the available time with the available work. If the supervisor has too much time, he will fill up the time somehow. Complaining about too much work is also a common habit. Therefore finding the right level is a challenge.

In the worst case, the supervisor (or the worker in general) gets used to the situation of having too much or too little time. He may see wasting time (if too much time) or making sloppy jobs (if too little time) as the new standard. You would not only need to adjust the workload or time, but also the attitude of the supervisor toward work. Overall, this topic has lots of options to mess things up, which DOES happen regularly in industry.

Effects Impacting Leadership Span

Here is an overview of the most important factors impacting the leadership span.

Complexity of the Supervision

One aspect impacting group size is the complexity of the supervision. Some things are easy to supervise, and the supervisor can manage multiple people. Other jobs require a lot of close supervision. This depends on the skill of the subordinates (see next point), but also on the complexity of the task at hand.

For example, consulting requires a lot of close coordination between team members. At McKinsey, we usually worked in groups of 1 to 3 people below the first level of management, since a lot of coordination was required, including coordination with the people of the client even if they were not part of our team.

An assembly line where every part is the same can be supervised easier than a line where every product is different. The more similar the tasks, the easier to supervise.

Independence of the Subordinates

Another factor is the level of independence of the subordinates. Do you manage a team of beginners who need constant supervision and coaching? Or is it a group of experts who are best left alone after giving them the basic outline of the task? Naturally, it is more time consuming to handle newbies than seasoned experts.

Another factor is the level of independence of the subordinates. Do you manage a team of beginners who need constant supervision and coaching? Or is it a group of experts who are best left alone after giving them the basic outline of the task? Naturally, it is more time consuming to handle newbies than seasoned experts.

Location of the Task (Ease of Communication)

Another factor is the location of the task. Are all people close at hand, ideally in the same room? In this case the manager can assist any needs quickly, and can switch between different employees quickly. Communication can be fast. Clues can be picked up non-verbally (employee getting nervous: Go and ask!). The supervisor can communicate with different people in short succession.

If the employees are more distributed, it is more difficult to supervise. The supervisor may have to do a lot more walking around, which consumes time. Getting information is also more time consuming for the same reason.Overall, the more distributed the employees are, the harder it is for the supervisor to actually supervise, since the communication requires more effort.

If they are working off site, it may be impossible to do supervision. The supervisor may be able to accompany one off-site worker, but cannot attend to any other workers at the same time. In this case it is common to pair an experienced worker with a newbie to teach him the ropes and be sort-of supervisor.

Continuous Improvement (Kaizen)?

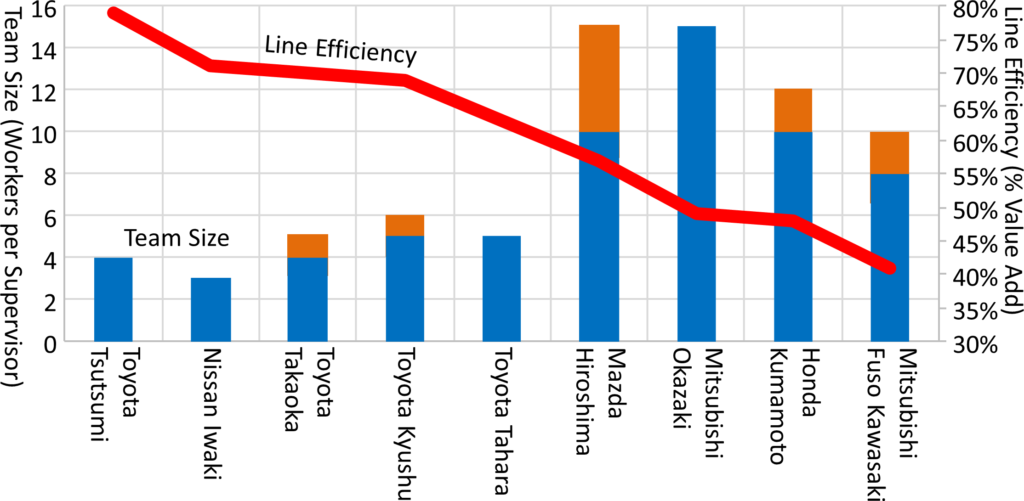

One of the (often forgotten) side jobs of a supervisor is to work on continuous improvement, both on his own and with his team. Here I have data on an interesting correlation. I measured efficiency (as the percentage of value adding time at assembly lines) and compared it with the lowest-level team size on the shop floor. For the full data see my Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive. The efficiency (red line) and the team size (blue bars with orange for the range of team sizes) is shown below.

Most curiously, plants that worked with smaller teams were much more efficient (i.e., the workers used more of their time actually working on the product rather than walking, waiting, transporting, or talking). And this included the supervisors at the line. Of course, correlation does not mean causation, but I do like to think that there is some connection. I believe smaller teams have more time to work on improvements to make the process faster, better, and cheaper.

It also matches my experience that an overloaded supervisor will drop optional things, with improvement work often being considered optional. I strongly disagree with this, but if I would be a shop floor team supervisor, I too would under time pressure put more effort into keeping the line running rather than improving the line, since I would get yelled at much more for a stopped line or late deliveries than a possible improvement project.

Other Workload of the Supervisor

Also do not underestimate the other workload of the supervisor. To give you a few examples from the shop floor, he may be responsible for data entry into the ERP system. He may be the first contact for maintenance and repairs. He could be the one planning the work schedules and absences. He could have to cover unplanned absences. He is usually the one looking for missing material. And so on. While many of these tasks are often not recognized at the higher levels of management, they are essential for a properly functioning shop floor.

Also do not underestimate the other workload of the supervisor. To give you a few examples from the shop floor, he may be responsible for data entry into the ERP system. He may be the first contact for maintenance and repairs. He could be the one planning the work schedules and absences. He could have to cover unplanned absences. He is usually the one looking for missing material. And so on. While many of these tasks are often not recognized at the higher levels of management, they are essential for a properly functioning shop floor.

Some Examples

In Japan, many automotive plants have a shop floor supervisor in charge of 3 to 15 people. Smaller teams seem to indicate better performance, as the supervisor has more time to help, fix, and especially improve things. Information flows faster and better in both directions, since a manager managing 5 people actually has time for his people!

In German automotive, a lowest-level supervisor often covers 20 to 25 people – on top of data entry, material search, organizational stuff, maintenance, and many other things. He simply has no time for his people to manage them properly. Additionally, the workload does go up more than the number of people. If you double the number of people supervised, you more-than-double the work for the supervisor. This would yet be another reason for smaller teams.

In the past, there was often a span of control of around 4 workers per supervisor. Nowadays it is rare to find a supervisor in charge of less than 10 people, and often even more. It is argued that modern communication makes communication easier and allows for easier supervision, and there is definitely some truth in that. However, I argue that another factor is continuous pressure to be profitable. Since the value of a supervisor cannot realistically be determined by cost accounting, cutting supervisors was seen as an easy way to cut cost. Unfortunately, reducing supervisors not only cut cost, but may have cut efficiency and productivity even more.

Overall, I do not have you an easy rule for the span of supervision. There are some available in literature, but I am not sure how valid they are. However, if you are a Western company, in all likelihood your span of supervision is too big. But equally likely, you will not have the money for more supervisors. Nevertheless, go out, try to reduce the span of control, and organize your industry!

This is a very interesting topic. During the Lean era many (even most?) Western companies have reduced the middle management levels. The result is that the remaining managers must supervise more and more employees.

To me supervise doesn’t really include develop. The more experienced employees that one has the less supervision is needed, but the need of development never ends. The more reportees one has the less time for their development.

When I participate in discussions regarding the number of reportees I usually refer to what I’ve learned by reading HR articles etc. A normal number of reportees that is mentioned is five to nine. Larger teams can neither be supervise nor developed, The manager just won’t have the time.

As a manager, at least in larger companies, must also “prove” to the company that you as a manager really follow all procedures that the HR department has introduced to makesure that the managers supervise and develop the reportees.

These procedures can be very time consuming and the more reportees that one has the more time one will need to fulfil all requirements. If one doesn’t send in all reports on time HR will be breathing down your neck.

I very often use the military as an example. A military is organised in groups, platoons, companies, regiments etc. The “managers” of these parts very often have seven to five to nine reportees. It’s the same all over the world, and has been for a long time. Is it because the military is old fashioned or that the experience is that this seems to be reasonable number?

Is it just a coincidence that the size of the Toyota teams have a similar size range?

1. I would have said 7, like Marti, based on military spans.

2. What is meant by ‘supervisor’? Many companies have Team Leaders who are semi-direct – i.e. they may be partially-loaded (a part-assignment or be relief operator). In Germany, Meister is a profession, rather than rank and wouldn’t be hands-on, although their Vorarbeiters (Foreman; =Team Leader) might again be semi-direct.

There are actually some academic papers trying to get data to determine a good span of control. Many of these papers give a span of 7 to 9 as good. This also seems to fit the span of control in Military. The science behind it however is always a bit fuzzy.

As for Meister, it is a technical certificate that this person is allowed to train others in his/her craft. It is well respected in Germany. In Industry, a Meister is often used as a manager on the shop floor, a level somewhere between the foreman and the shop floor manager, sometimes even being the shop floor manager. However, there are also many Meister that run their own little company with a handful of employees.