Fluctuations are bad for manufacturing. In lean, unevenness is one of the three evils, besides waste and overburden. In this post I will give you an introduction to fluctuations. One option to handle fluctuations is decoupling, but this addresses only the symptoms and not the cure. In my next post I will show you how to actually reduce fluctuations.

Fluctuations are bad for manufacturing. In lean, unevenness is one of the three evils, besides waste and overburden. In this post I will give you an introduction to fluctuations. One option to handle fluctuations is decoupling, but this addresses only the symptoms and not the cure. In my next post I will show you how to actually reduce fluctuations.

Introduction

Fluctuations are part of all production systems. Fluctuations are actually part of everything. According to the second law of thermodynamics, entropy (disorder) can only increase in a closed system. Over time, everything, the whole universe, drifts toward chaos. Unfortunately, this includes your shop floor. It takes energy to reduce the chaos on your shop floor, but as soon as you stop taking care of your shop floor, chaos will increase again. Even with your best efforts, you cannot eliminate chaos completely, only reduce it. Hence, keeping fluctuations in check is a never-ending task on your list of to-do’s.

Fluctuations usually happen randomly. A machine breaks. A delivery is late. A customer buys a product (which, in itself, is not bad, but the irregularity in which it happens can cause problems). Other fluctuations are not random and may be, for example, cyclic like seasonality, or even planned like a not-leveled production plan. Any deviation from perfect monotony is a fluctuation. You won’t be able to avoid all fluctuations. Even with lot size one, you will produce different products, whose different requirements and needs are a fluctuation.

Fluctuations usually happen randomly. A machine breaks. A delivery is late. A customer buys a product (which, in itself, is not bad, but the irregularity in which it happens can cause problems). Other fluctuations are not random and may be, for example, cyclic like seasonality, or even planned like a not-leveled production plan. Any deviation from perfect monotony is a fluctuation. You won’t be able to avoid all fluctuations. Even with lot size one, you will produce different products, whose different requirements and needs are a fluctuation.

The big issue with fluctuations is, unfortunately, that they do not stay in place. If you throw a stone in a pond, there will be a local splash, but also a wave that goes across the pond. Similarly, in a production system a fluctuation will run through the value stream, both upstream and downstream. A machine breakdown will empty inventory downstream, subsequently cause machine stops, and can eventually lead to a missed sale or a late delivery. The same breakdown fluctuation also travels upstream, filling up inventory, subsequently also stopping preceding processes, and even could lead to canceling an order with your supplier.

The big issue with fluctuations is, unfortunately, that they do not stay in place. If you throw a stone in a pond, there will be a local splash, but also a wave that goes across the pond. Similarly, in a production system a fluctuation will run through the value stream, both upstream and downstream. A machine breakdown will empty inventory downstream, subsequently cause machine stops, and can eventually lead to a missed sale or a late delivery. The same breakdown fluctuation also travels upstream, filling up inventory, subsequently also stopping preceding processes, and even could lead to canceling an order with your supplier.

The ripple doesn’t stop there. Both your customer and your supplier will be impacted by your fluctuations through the delayed or canceled order. Hence, this simple machine breakdown fluctuation can travel quite far in both directions of the value stream, even if the original cause may no longer be visible. Systems outside the value stream may also be affected. The machine breakdown may require additional efforts by maintenance, which may lead to a postponed planned maintenance somewhere else, which in turn may cause other problems.

Even worse, in some cases the fluctuation may increase. The affected systems try to manage the fluctuation, and inadvertently make it worse. Along supply chains this is known as the bullwhip effect. Overall, fluctuations are not good, but fluctuations traveling up and down (and sideways) on your value stream are really bad. A lot of the fluctuations you have on your shop floor originate from outside of your shop floor (although, don’t worry, you also create fluctuations for others and give them a headache, too).

Even worse, in some cases the fluctuation may increase. The affected systems try to manage the fluctuation, and inadvertently make it worse. Along supply chains this is known as the bullwhip effect. Overall, fluctuations are not good, but fluctuations traveling up and down (and sideways) on your value stream are really bad. A lot of the fluctuations you have on your shop floor originate from outside of your shop floor (although, don’t worry, you also create fluctuations for others and give them a headache, too).

In lean language, this is one of the three fundamental evils in manufacturing. You probably know waste (無駄, muda). But there is also overburden (無理, muri) and – relevant here – unevenness (斑, mura). While overburden is considered the worst, unevenness is the second most important evil to fight. Mura can be translated as unevenness, inconsistency, erraticness, irregularity, or lack of uniformity.

In lean language, this is one of the three fundamental evils in manufacturing. You probably know waste (無駄, muda). But there is also overburden (無理, muri) and – relevant here – unevenness (斑, mura). While overburden is considered the worst, unevenness is the second most important evil to fight. Mura can be translated as unevenness, inconsistency, erraticness, irregularity, or lack of uniformity.

It may not sound exciting, but you want your shop floor to be boring! In most cases, the fewer fluctuations you have, the better your system will run. (An exception where monotony would be bad is, for example, perfectly stable customers that consistently never order anything.) While some people live and breathe firefighting, not having to firefight in the first place is actually much better.

What About Decoupling?

Fluctuations are much worse since they travel up and down the value stream. Hence, one possible way to work with fluctuations is decoupling. While the fluctuation still exists, decoupling will reduce the impact of the fluctuations on other parts of the system. In a way, you reduce the impact of fluctuations on others. In the best case you may even isolate the fluctuation to its origin, and have no other systems affected.

Fluctuations are much worse since they travel up and down the value stream. Hence, one possible way to work with fluctuations is decoupling. While the fluctuation still exists, decoupling will reduce the impact of the fluctuations on other parts of the system. In a way, you reduce the impact of fluctuations on others. In the best case you may even isolate the fluctuation to its origin, and have no other systems affected.

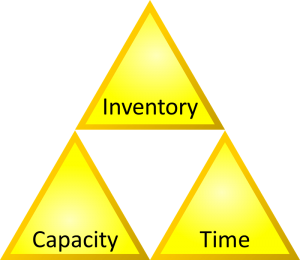

Sounds good, right? Well, you are already doing it to some degree. There are three fundamental ways to decouple fluctuations. For more, see my post on The Three Fundamental Ways to Decouple Fluctuations. The best known is inventory. You buffer fluctuations through inventory. If there is a disruption, buffers may keep other processes working by filling up or emptying, depending on the location. The larger the buffer, the better its ability to decouple fluctuations.

The second way to decouple fluctuations is capacity. You change the work time of your machines and workers to match the changes in demand. This is also done to some degree, but requires more effort and ideally an advanced notice.

The third way to decouple fluctuations is time. This is usually the default fallback if the other two approaches were insufficient. In effect, machines, workers, or customers wait until the issue is resolved. If you do nothing, time will take care of your fluctuations. Like ripples on a pond, they will eventually stop. Unfortunately, this is often the least desirable outcome. You usually don’t want your machines and workers standing around doing nothing.

Sooo … if buffers decouple fluctuations … why don’t I just put big buffers everywhere? Problem solved, right? Well, unfortunately no. Big buffers will decouple fluctuations in the material flow, although possibly not all. However, they come at a cost. There is the tied-up capital and the used storage space. But there are many more negative effects of inventories, including an increase of the lead time, administrative overhead, delay in the information flow, handling, aging and subsequent crapping and obsolescence, and more.

Similarly with just having tons of capacity available. Having extra machines and workers for the occasional fluctuation is also expensive, and hence it is done sparingly. Firefighters spend a lot of time waiting, but you don’t want to run out of firefighters in an emergency. But for most manufacturing systems, this is only a limited option.

Overall, while you can decouple fluctuations, it does not address the problem, but only the symptoms. It also costs time and money. Lean is known (among other things) for reducing inventory. The idea is to reduce it to the inventory you need to decouple (most) fluctuations, and then to reduce the fluctuations itself so you can reduce the inventory even more. Hence, reducing fluctuations is more important than reducing inventory.

After this lengthy introduction on why fluctuations are so important, my next posts will look into how to reduce these fluctuations. But, please, don’t expect miracles. Reducing fluctuations is a difficult, grueling, and never-ending effort. They are also a myriad of different causes of fluctuations. Now, go out, get those fluctuations under control, and organize your industry!

Series Overview

- Why Are Fluctuations So Bad?

- Structure for Reducing Fluctuations

- Reducing Fluctuations Upstream

- Reducing Fluctuations on Your Shop Floor

- Reducing Fluctuations Downstream

Excellent description of the problem, easy to understand!

Great article!

I think that the modern enterprise, which requires more and more customization, flexibility and shorter lead times, needs more capacity buffers, rather than inventory or much less lead times … and I don’t know if Industry 4.0 is able to satisfy this need.

What do you think about it?

Hi Sando, as you may know from reading my blog, I am not so hot on Industry 4.0. Some stuff helps, others is hot air. Capacity (and inventory and time) only decouples the fluctuations. The real gold is in REDUCING the fluctuations 🙂

Factory Physics describes Lean as being “fundamentally about minimising the cost of buffering variability (read fluctuations)”.

Looking forward to the next post on how its done.

Great post and great understanding of the issue. As a supply chain student, fluctuations up and down the value stream are not mentioned as often as you think. It may be different vocabulary being used, but this post about fluctuation makes it very easy to understand.

Hi Spencer, fluctuations (or Mura in Japanese) is not often mentioned, because there is no quick and easy way to reduce fluctuations. There is no method like SMED or so that tackles this issue. It is tedious, despite being necessary, but it is not a facourite of the consulting industry.

Fluctuations are a very big part of supply chains. As a student, there have been many examples I have heard regarding fluctuations whether they concern the automobile industry during COVID, or the significant difference in Amazon ordering after the holidays. I enjoyed reading this post very much as I could relate it to many examples and topics I’ve learned, and also about the ways to decouple fluctuations.

Hello Christoph,

I really enjoyed your article on fluctuations and your breakdown and thoughts on what causes these fluctuations are such a great frequency. I fully agree on your areas of focus when it comes to dealing with fluctuations, snd inventory, capacity, and time are certainly areas of great importance when it comes to fluctuations within the industry. It is crucial to be efficient in these areas if a company wishes to succeed despite fluctuations in the market.

Hi Christoph,

My name is Evan and I am a senior in college where I study Business, Computer Science, and Spanish. I am currently pursuing my Green Belt certification which led me to stumble upon your blog post here.

Foremost, I had never heard of the “three evils” before. In class, we generally look at discussing the 8 wastes using the DOWNTIME model, and we learn how to measure, analyze, and improve upon the processes. The three evils idea was new to me and makes me want to dig into the details of fluctuations and overburden.

I enjoyed your anecdote regarding the law of thermodynamics, and how entropy only exists in closed systems. I think it is a good perspective to view machine breaks, late deliveries, and purchases as fluctuations so you can properly plan for them or at least know how to react when they occur. You also took it further with your pond analogy, which I think is a great way to demonstrate how a fluctuation at one point can move upstream and downstream. You even demonstrated how fluctuations can affect other value streams, which I think is interesting to consider.

I also liked reading your segment on “decoupling” a value stream via inventory, capacity, and time. I had never heard of these decoupling strategies, and I liked how you analyzed the pros and cons of them, including how decoupling can lead to an increased lead time, administrative overhead, delays in information flow, handling, and obsolescence.

I agree that reducing fluctuations is a never-ending task, just like the rest of Lean in our continuous improvement mindset. I am looking forward to reading your next article regarding fluctuations. While I am at it, do you have any resources for me from which I can learn about overburden? I really enjoy the muri, muda, and mura framework, and I would like to hone out my scope to learn more about these evils.

Sincerely,

Evan

Hi Evan, many thanks for the long comment. Reading it made me smile, because my message seems to come through (and is appreciated) 🙂

Many thanks, and keep on reading!

Chris