Two hundred fifty years ago today, clockmaker Eli Terry was born on April 13, 1772 in (what is now) South Windsor, Connecticut, USA. He was one of the earliest industrialists using mass production with interchangeable parts in the USA, contemporary with the better-known muskets of Honoré Blanc in France (ca. 1785), and long before John Hancock Hall at the Harpers Ferry Armory (ca. 1824). His name is known mostly to nerds in manufacturing and horology, but I believe his achievements deserve recognition. Hence I will go back in history to look at his life.

Two hundred fifty years ago today, clockmaker Eli Terry was born on April 13, 1772 in (what is now) South Windsor, Connecticut, USA. He was one of the earliest industrialists using mass production with interchangeable parts in the USA, contemporary with the better-known muskets of Honoré Blanc in France (ca. 1785), and long before John Hancock Hall at the Harpers Ferry Armory (ca. 1824). His name is known mostly to nerds in manufacturing and horology, but I believe his achievements deserve recognition. Hence I will go back in history to look at his life.

On Clocks…

Measuring time has always been of interest to humanity. From the sun (or its shadow) to water clocks, marks on candles, hourglasses with sands, to mechanical gears. But these required effort and often were quite expensive. Clocks on church towers and other public buildings were sort of a service to the public so everybody could check the time. A clock at home was affordable only to the rich. Clockmakers in America started making clocks from the 18th century onward.

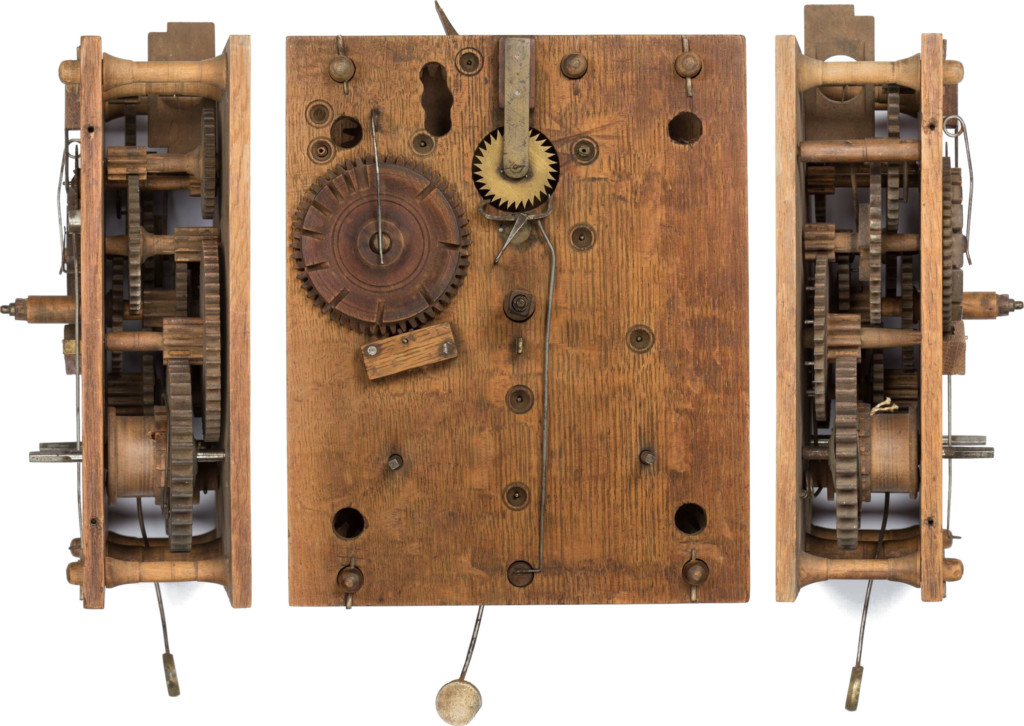

Since metal was rather expensive back then, many clocks were mostly made of wood, and only crucial parts were made of metal. Even then, the components for clocks were painstakingly filed by hand, and fitted together with even more frequent adjustments and filing. It was a luxury piece affordable only to the wealthiest, and custom made on order. A skilled clockmaker was able to make around six to ten clocks per year, with a clock costing around €400–900 in nowadays prices.

The Early Years of Eli Terry

Eli Terry was born on April 13, 1772, to Samuel and Huldah Terry in South Windsor, Connecticut, USA (at that time his birthplace was part of East Windsor). He apprenticed as a clockmaker. Unusually, he apprenticed both for brass and wooden clocks. Afterwards, in 1792, at age twenty, he started his own business in Plymouth, Litchfield County, making clocks slowly and laboriously by hand just like every other clockmaker of his time.

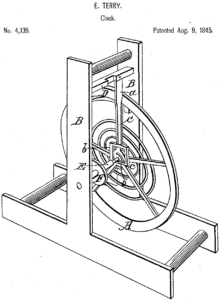

However, in 1795 he developed a simple machine that mechanized the cutting of the gears. Rather than making the gears (painstakingly) individually, the machine milled a tooth for multiple gears at once using a circular saw. The machine then moved to the next position for a tooth and cut another tooth. A whole batch of gears was produced simultaneously and quickly.

Since wooden gears required less precision than metal gears, almost by accident, this made his parts interchangeable. In turn, this allowed him to produce many more clocks than before. But this still pales in comparison to the mass production that he was to venture into.

Mass Producing Clocks

In January 1806 Terry expanded and built a small factory. This factory was water powered, and is considered the first water-powered shop in the US. Terry improved on his tools using different jigs and fixtures. He substituted water power for apprentices, and used journeymen to finish the gears. He also installed water-powered saws and lathes to speed up production even more.

He then promised two merchants that he would produce an unheard number of 4000 clock movements within three years. A conventional clockmaker would need more than 400 years to make this number of clocks! And Terry promised it in three years! A very bold statement. Especially since his factory was too small. He needed to expand even more. In June 1806 he established a much larger factory. The ramp-up was not easy, and it took him two years to get everything running smoothly.

But then his output took off like the world had not seen before. He was able to produce 3000 clocks per year, not only tremendously faster than other clockmakers, but also tremendously cheaper! His factory was a stunning success, and was a license to print money. But that was not what Terry wanted. After he fulfilled his contract of 4000 clocks, he sold the factory to his assistants in 1810 at age thirty-eight. Afterwards he retired with a modest fortune to do what he loved… tinkering with clocks.

Coming Out of Retirement

In 1812 he came out of retirement and started another clock factory, with a focus on ease-of-use, machined parts, interchangeability, and low cost. From 1814 onward, Eli Terry mass-produced truly interchangeable clockworks and clocks, one of the first examples of true interchangeability in the world and almost certainly the first in the USA. Soon hundreds of men worked for Terry in his factory.

This revolutionized clockmaking in the USA. While before a clock cost around $20–$40 (roughly $400–$900 in today’s currency), Terry managed to drop the price to around $10, and later even lower to $5. While wooden clocks were a luxury item before, they became standard for the middle class by 1830. By then, pretty much no small clockmaker was left in the business, as Terry and his three largest competitors produced 15 000 wooden clocks every year from 1820 onward.

Patents

During his tinkering, he improved the mechanism of the clocks. He received at least five patents throughout the years and had the first US patent for a clock, trying to secure his intellectual property. However, like many other inventors, he found out the hard way that having a patent and benefiting from a patent are quite different. Other clockmakers soon copied Terry’s design, and a whole industry was created that supplied parts and built clocks based on Terry’s ideas.

Some copycats even advertised their plagiarism as “Patent Clocks”! In some cases Terry took action, and for example he successfully sued the Reeves & Co company that plagiarized his clocks, forcing them out of business and had their stock of unsold clocks destroyed. But his work continued to be copied.

Retiring Again

Terry became very rich with his business. However, it was not what he wanted, and in 1820 he retired (again) (other sources say 1833). He did what he forced others to quit, making custom clocks by hand. His workshop was one of the last traditional clock shops, as he had forced everybody else out of the business. He died on February 24, 1852, at the age of eighty-one. Three of his sons followed in his footsteps and also became clockmakers.

Overall, he destroyed old-style clockmaking, but at the same time he made clocks affordable for everyone using mass production and interchangeable parts. He was definitely a pioneer in manufacturing! Now, go out, follow his footsteps by making your products less expensive, and organize your industry!

Thanks for the interesting history on clockmaking and manufacturing – there is a town in CT called Terryville near to Litchfield CT and also Thomaston, CT after Seth Thomas – another famous clockmaker from CT. That area of CT really benefited from the ingenuity of Eli Terry and that whole area of CT became a center for copper and brass production. Thank you for sharing.

Interesting story. Thanks for sharing.

Great story! Thank you for sharing the unheard story of a mass production pioneer. Though Eli Terry singlehandedly destroyed the clock industry, he was able to make parts extremely cheap and start the movement of making standardized parts in large quantity. In turn he helped spread the availability of clocks and potentially spark the idea of making batched goods for cheaper prices. From Eli Terry I feel the next big pioneer would be Henry Ford who then moved this similar idea into a line of workers that created a standardized product for cheap.

Many thanks – all new to me. I had thought the pioneers of mass production were the people making blocks & tackle for sailing ships, followed by Remington. Live & learn though!

Great story. I had no clue about it. It is very interesting to know all those people who worked hard in their fields and made advances in production techniques. Have a nice day!

Many thanks to all for the nice feedback 🙂

I have an old SB Terry weight driven regulator that I can’t find anything about. It has a octagon top. The dial had to be replaced and it has had some work on the case to restore it. I would also like to know it’s value. I think it is pretty rare. It is around 42 inches long.

Eli hired young Seth Thomas as a clockmaker apprentice.

Seth fell in love with Eli’s daughter and they eloped.

With him, he took not only Eli’s daughter—he took his father-in-law’s teachings and established his own factory and eventually bought out Eli’s old business.

Thomaston, Connecticut is named after Seth.

Hi Gerald, interesting bit of history. I did not know that. Thanks for sharing!