Nissan by itself would be the sixth-largest car maker (5.5 million vehicles in 2016), although it is now a part of the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi alliance, which was the largest car maker in 2017. It is also the world’s largest producer of electric vehicles.

Nissan by itself would be the sixth-largest car maker (5.5 million vehicles in 2016), although it is now a part of the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi alliance, which was the largest car maker in 2017. It is also the world’s largest producer of electric vehicles.

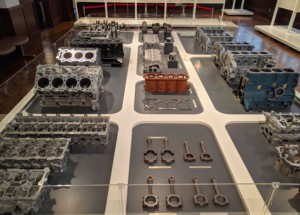

As part of my grand tour of Japanese automotive plants, I visited their Yokohama and Iwaki plants, which both make engines. In my view, the manufacturing performance of Nissan is comparable to that of Toyota, making it also one of the most efficient car makers worldwide. Let me show you what I found.

Introduction

Nissan started out as a holding company in 1928. They owned foundries and automotive suppliers. In 1933 they took over another company, which included the first Japanese car maker, DAT. Together with other companies, the Nissan group founded Nissan Motor Co. in 1934. Its first plant in Yokohama started operating in 1935.

Now, here it gets interesting. All other Japanese car companies had a Japanese inventor or tinkerer behind it. While the founder and CEO of Nissan, Yoshisuke Aikawa, was very interested into cars, the actual driver behind the technological progress at Nissan was an American engineer, William Gorham (1888–1949).

Born in San Francisco, Gorham visited Japan many times together with his father. After graduation he founded an engineering company. Seven years later in 1918, however, he moved to Japan together with his family. He worked for numerous engineering and automotive companies connected to Nissan in Japan, but also for Hitachi and Canon. He changed his citizenship to Japanese at the onset of World War II to avoid deportation, taking the name Gorham Katsundo (合波武 克人).

His work was very influential. He introduced numerous American methods for design, development, and production. He imported numerous machines and entire assembly lines from America. From a technological point of view, Gorham was the godfather of Nissan, and is still held in high regards at Nissan. Hence, Nissan was strongly influenced by American technology from early on, much more so than other Japanese car makers.

This foreign influence continued. During the economic crisis in Japan in 1990, Nissan almost went bankrupt. To improve their situation, Nissan partnered up with Renault in 1999. Renault is here the stronger partner, as Renault holds 43% of Nissan’s voting shares, whereas Nissan holds only 15% of Renault’s non-voting shares (as of 2018).

This introduces the second highly influential foreigner at Nissan, Carlos Ghosn (born 1954). He turned Michelin around, rescued Renault, and is known as “Le Cost Killer.” He became the CEO of Nissan in 2001. His “Nissan Revival Plan” brought the company back to profitability within only twelve months.

He also seriously disrupted the corporate culture at Nissan. He introduced promotion based on performance rather than seniority, ended the lifetime employment, dismantled the Nissan Keiretsu (business group), and got rid of under-performing suppliers. Despite that, or maybe even especially because of that, he has a very high reputation in Japan, and his leadership style is highly admired.

Overall Impression

When visiting both the Yokohama plant and the Iwaki plant, I saw two high-performing automotive plants, the only plants in Japan with a performance level similar to Toyota. Both plants looked very clean, although the Yokohama plant had a strong smell of oil and gasoline.

When visiting both the Yokohama plant and the Iwaki plant, I saw two high-performing automotive plants, the only plants in Japan with a performance level similar to Toyota. Both plants looked very clean, although the Yokohama plant had a strong smell of oil and gasoline.

Yet, after visiting dozens of Japanese automotive plants, Nissan plants feel a bit different. One thing is the higher level of automation that I observed in both plants. Early on, Nissan moved toward robotics and automation, and has much higher levels of automation than many other automotive plants.

A second difference is harder to pin down. To me, it somehow … felt more like an European or American plant rather than a Japanese plant (despite almost all workers being Japanese and the plant being more efficient than European or American plants). I am not quite sure myself why I had this impression. Maybe it is because many other Japanese automotive plants have many quick fixes slapped together with some plastic tubing and string to help with assembly. Nissan, on the other hand, uses more-refined technology by bolting together metal profiles. Both approaches work, with Toyota’s being cheaper but Nissan’s being more sturdy. Maybe this is because Nissan was strongly influenced by Gorham and Ghosn.

Information Flow

The information flow at Nissan is overall well organized, using kanban for a pull system. There are different andon throughout the factories, as well as an andon stop buttons or cords at the final assembly lines. The assembly lines work in small teams with one supervisor. The supervisor was always circling around behind his people, ready to jump in whenever there is a problem. Curiously, at Iwaki there were only three workers per supervisor, whereas in Yokohama there were six to eight people per supervisor (Toyota usually around four to five).

Kaizen improvement activities were also quite visible, maybe even more so than other Japanese auto makers, with lots of A3 sheets at different meeting locations throughout the factories. They also often use pointing and calling.

At both plants, Nissan has a board with a wooden slate for each worker or supervisor in the plant. These are nicely printed, and quite fancy. They use it for planning and organizing of the team structure. While such plans are common, only at Nissan did I see such high-quality wooden name tags rather than paper or printed magnets.

Material Flow

The material flow is mostly well organized. Material transport is mostly by AGV, following magnetic tapes on the floor, unless it is automated conveyors overhead, underground, or on top of the floor.

Karakuri Kaizen is common, often with cute names for the karakuri gadgets like “oiwa-san” (お岩さん, Mr. Big Rock) or “ippatsudashi-kun” (一発出し One Punch Out Buddy). They also like to give some of their machines fancy colors, and a robot was painted to look like a giraffe.

At the Iwaki plant, I did see some pallets that felt “dumped” on the middle of the path, indicating that their standard, while good, is not perfect. Both plants seems to have larger inventories than at Toyota.

Efficiency

Nissan plants are usually highly automated. For example, at the milling shop, only five employees took care of two hundred machines. The performance of the assembly lines were also excellent. I estimated that around 70% of the time, the employees add value to the product in both Iwaki and Yokohama. This is close to Toyota’s 70% to 90%,and much better than the industry average of 50% to 60%. The engine assembly lines had a takt of around fifty seconds in Iwaki and sixty to seventy-five seconds in Yokohama.

Nissan plants are usually highly automated. For example, at the milling shop, only five employees took care of two hundred machines. The performance of the assembly lines were also excellent. I estimated that around 70% of the time, the employees add value to the product in both Iwaki and Yokohama. This is close to Toyota’s 70% to 90%,and much better than the industry average of 50% to 60%. The engine assembly lines had a takt of around fifty seconds in Iwaki and sixty to seventy-five seconds in Yokohama.

Comfort

The working times at Yokohama were 8:00AM to 3:00PM and 8:00PM to 3:00AM, giving a five-hour gap between the shifts. This is ideal for maintenance, but difficult for workers especially on the late shift, and Toyota stopped using this method in the 1990s. At Iwaki they had only one shift for the assembly line from 8:30AM to 5:30PM. The foundry worked around the clock in two shifts from 8:30AM to 8:30PM and 8:30PM to 8:30AM, with four days of work followed by two days off. The aggregation site Vorkers.com ranks Nissan pretty high with an overall grade of 3.5 out of 5.

If You Want to Follow in My Footsteps …

Reservations for visits to Nissan factories can be made through their website, but this requires some knowledge of Japanese, as they do not offer English tours. The Yokohama factory I visited is their oldest factory, and their visitor center is a pre-war historic office building.

Reservations for visits to Nissan factories can be made through their website, but this requires some knowledge of Japanese, as they do not offer English tours. The Yokohama factory I visited is their oldest factory, and their visitor center is a pre-war historic office building.

The Iwaki plant is their smallest factory with only 750 employees. Both produce engines, with Iwaki focusing on larger engines for larger cars, and hence due to the smaller demand operates only one shift for the engine assembly (their aluminum foundry is staffed around-the-clock as most foundries in the world). I was also able to see this aluminum foundry, which is usually not part of a plant tour. They claimed that their two-minute cycle time at the foundry was the world’s fastest for engine blocks.

The Iwaki plant is located in Fukushima, and is only 60 km away from the Fukushima nuclear power plant that was destroyed in the 2011 tsunami, but the plant is outside of the restricted zones. The plant itself was heavily damaged by the earthquake, but was high enough to avoid the tsunami and reopened after only two months. As the floor shifted vertically up to 10cm, the current floor has some odd slopes where they repaired this offset. As there are still aftershocks, the remodeled floor also has lots of smaller cracks.

The Iwaki plant is at 386, Shimokawa-aza-Otsurugi, Izumi-cho, Iwaki-shi, Fukushima 971-8183, and the Yokohama plant at 2 Takaracho, Kanagawa, Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture 221-0023.

Summary

Overall, Nissan automotive plants have an outstanding performance comparable to Toyota, despite their different approach using much more automation. I believe that Nissan plants are also among the world’s best automotive plants, besides (behind?) Toyota. I definitely enjoyed the visit (but then, I am a geek for such kind of things). Now, go out, and organize your industry!

Series Overview

- The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive – Overview and Toyota

- The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive – Nissan

- The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive – Honda Sayama

- The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive – Honda Kumamoto

- The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive – Mitsubishi

- The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive – Mazda

- The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive – Suzuki

- The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive – Subaru

Many thanks. As a NMUK alumnus I’m always keen to hear how NML is doing, and its nice to hear comparisons with Toyota which gets a heck of a lot more press. Historically, Nissan’s strategy to sell abroad, then assemble abroad, then manufacture, then design etc. abroad I believe has been ahead of Toyota, although in volume terms it was overtaken during the mid-1960s. Even in the 1980s when I joined, culture at different plants varied according to their histories, so there wasn’t the family single-mindedness perhaps to be found at Toyota.

Senior people had a soft spot for England, as they were pleased to acquire the licence to make ‘Baby Austins’ in the 1950s, and then much admired the plant at Longbridge, and aspired to having one like that themselves one day!

The book ‘The Reckoning’ comparing the growth of Ford and Nissan made interesting reading 30 years ago, although much has changed since then.

Hi Steve, having not paid too much attention in the past to Nissan since “Toyota [] gets a heck of a lot more press”, I was a bit surprised how good Nissan was. I will try to look more into Nissan and visit more Nissan plants in the future.

I also just read that Nissan wants to buy more shares of Renault to prepare a possible merger. Interesting, I guess I have to check out Renault, too. Thanks for commenting!

Thanks for the post! I didn’t know the history about the American engineer. Fascinating tour report.

Hi Mark, many thanks 🙂

Great site of yours, by the way: leanblog.org

Promised my son a trip to Japan, all things Nissan, as a college graduation gift. No idea where to start. Any advice?

Hi Dina, only Toyota in Toyota City and Mazda in Hiroshima offer English language tours. For Nissan there are (to my knowledge) only Tours in Japanese, and a basic skill of Japanese is needed. You may want to hire an interpreter. As for the factory tours, this page lists the Nissan Plant tours in Japan and details on its reservations. You can look at it with Google Translate, maybe. Good Luck!