Standards are the result of problem solving. In this article I will talk more about how to write a standard, but this is the outcome or the last steps of the problem-solving process. From this post onward I will look more at work standards, although the following is applicable to a lesser extent to part standards. Again, a standard is not something done on its own, but is part of a problem-solving process.

Standards are the result of problem solving. In this article I will talk more about how to write a standard, but this is the outcome or the last steps of the problem-solving process. From this post onward I will look more at work standards, although the following is applicable to a lesser extent to part standards. Again, a standard is not something done on its own, but is part of a problem-solving process.

It’s All About Problem Solving!

A standard should not be done on its own. This would have the risk of creating a standard for the sake of having a standard, which is useless. Instead, a standard is the result of a problem-solving process. You must start by selecting a problem you want to solve! This could also be a foreseeable problem if you don’t have a standard, or an improvement potential that brings you other benefits.

A standard should not be done on its own. This would have the risk of creating a standard for the sake of having a standard, which is useless. Instead, a standard is the result of a problem-solving process. You must start by selecting a problem you want to solve! This could also be a foreseeable problem if you don’t have a standard, or an improvement potential that brings you other benefits.

Hence, the whole thing starts with a problem-solving process. Without going into too much detail, here is a brief overview of possible steps you can do. The links go to blog posts of mine with more details.

- Select a problem that is relevant and gives a good benefit for the invested effort.

- If applicable, create a team for the problem solving, including some people who later have to use the standard, and set up a workshop or on-site meeting (Gemba!).

- Start an A3 report. This will guide you through the problem-solving process. The following points are part of the A3 process:

- Analyze the current state and understand the problem.

- Define a goal.

- Do a root cause analysis to understand what causes the problem.

- Develop a solution, or – even better – multiple solutions and select the best one.

- Implement the solution, including preparation, timeline, etc. if needed.

- Check if a) the solution works, and b) you have reached your goal.

- If your goal has not yet been reached, understand why and continue to improve until you have achieved the goal. This would be the Check and Act of Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA), and failing to do so is in my view the primary reason for a failed lean project.

Only when you get to the end of this whole problem-solving process can you start to think about writing a standard. To be fair, the problem solving does not have to be fully completed, and you can already start writing the standard before you are done with the Check and Act of the PDCA; although in this case you have to update your standard if you update your solution. In general, there are two possibilities:

Only when you get to the end of this whole problem-solving process can you start to think about writing a standard. To be fair, the problem solving does not have to be fully completed, and you can already start writing the standard before you are done with the Check and Act of the PDCA; although in this case you have to update your standard if you update your solution. In general, there are two possibilities:

- If you start to write your standard during the “Do” part of the PDCA, then changes during the Check and Act need to be reflected in the standard.

- If you write your standard after the PDCA is completed successfully, you have to do a separate “Check” and “Act” for the standard to see if the standard is workable and actually describes your working solution well.

Both are possible, but I have a slight preference to already start writing the standard toward the end of the “Do” phase of the PDCA, but either way works. Now, let’s go into more detail on how to actually write the standard. There are a couple of points when writing a standard. Below are the first three, more in the next post of this series.

A Standard Is for Tasks or Items That Are Used Repeatedly

Standards are useful only if you use them more than once. If you do something only once, then there is no point in writing a standard. Luckily, pretty much all things in industry have at least some repeating elements. This is what you can standardize. If you produce custom injection molding tools, you do not write a standard specifically for a certain tool that you produce only once. However, you can write a standard about the general development process, or using certain milling machine specifications matching different mold materials, etc. Just as a side note, of course you can and sometimes even should write down what you did only once, but this a documentation, not a standard.

A Standard Should Find a Balance between Too Much and Too Little Detail

This is for two reasons. One is to provide the user of the standard with the necessary details while not overloading him with data garbage. The second one is to find a balance between the effort of making a standard and the benefit of having a standard. This is related to the frequency of the repetition. If you make the same part every 60 seconds, it may be worthwhile to write down the actions in great detail. I have used standards that detailed, in intervals of less than 10 seconds, what the right hand should do and also what the left hand should do, plus occasionally an eye or foot movement. This was possible because the work was also optimized on this level of detail. Again, this makes sense if you do the work very, VERY often. If you repeat the work less frequently, the standard has a much coarser guidance. If you produce one molding machine per week, you probably would not write down the actions for the left hand and the right hand for every worker in five-second intervals, but the standard could look more like a checklist and may not even have a time schedule.

This is for two reasons. One is to provide the user of the standard with the necessary details while not overloading him with data garbage. The second one is to find a balance between the effort of making a standard and the benefit of having a standard. This is related to the frequency of the repetition. If you make the same part every 60 seconds, it may be worthwhile to write down the actions in great detail. I have used standards that detailed, in intervals of less than 10 seconds, what the right hand should do and also what the left hand should do, plus occasionally an eye or foot movement. This was possible because the work was also optimized on this level of detail. Again, this makes sense if you do the work very, VERY often. If you repeat the work less frequently, the standard has a much coarser guidance. If you produce one molding machine per week, you probably would not write down the actions for the left hand and the right hand for every worker in five-second intervals, but the standard could look more like a checklist and may not even have a time schedule.

A Standard Must Be Easy to Understand

This is obvious, and also somewhat depends on the balance between too little and too much detail above. The standard is a written document (or sometimes an Ikea-style cartoon depending on the literacy and language abilities in your plant) that should describe the standard. Especially for work instructions it helps to have photos, other images, and diagrams. It can also benefit from visual management highlighting key aspects of the work. If you managed to include poka yoke (mistake proofing) in your problem solution, it will simplify your standard. Anything that can be done only one way by design does not need an explanation in the standard on the different ways it could have been done.

This is obvious, and also somewhat depends on the balance between too little and too much detail above. The standard is a written document (or sometimes an Ikea-style cartoon depending on the literacy and language abilities in your plant) that should describe the standard. Especially for work instructions it helps to have photos, other images, and diagrams. It can also benefit from visual management highlighting key aspects of the work. If you managed to include poka yoke (mistake proofing) in your problem solution, it will simplify your standard. Anything that can be done only one way by design does not need an explanation in the standard on the different ways it could have been done.

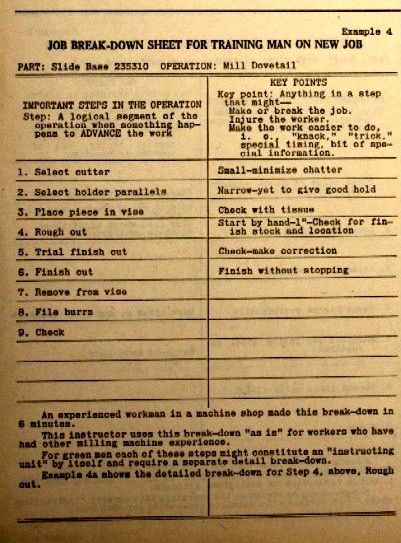

In general, it should outline the key steps of the work. But it should also go into more detail of key points. Below is an older standard from TWI for milling a dovetail. Notice the basic steps and the key points for some of them. Nowadays this could also include images and (very important for standardized work) the duration needed to do these steps.

These are the first few points on writing a standard, but there are more. I will continue this in my next post before also talking about how to improve a standard, and will eventually look deeper at the all popular standardized work for assembly or manufacturing operations. Now, go out, polish your standards a bit more, and organize your industry!

Series Overview

- Standards Part 1: What Are Standards?

- Standards Part 2: Why and Where to Do Standards

- Standards Part 3: How to Write a Standard

- Standards Part 4: How to Write a Standard (Continued)

- Standards Part 5: How to Use and Improve a Standard

- Standards Part 6: Standardized Work

- Standards Part 7: How to Write a Work Standard

- Standards Part 8: Example for a Work Standard

- Standards Part 9: Leader Standard Work

Source:

Many thanks to Osamu Higo for writing the excellent article Crucial Misconceptions on Lean – Standardization, which inspired this series of blog posts.

Very informational. Will apply methods going forward……

Thanks for valuable information

Professor,

Another post with valuable information. I found the section on the balance of detail very interesting. It is definitely an important step to consider. Striking the right balance of detail to simplicity cirtenly should be attached to how often and how complex the task is. Another important consideration must be, like you said, is how specific the rest of the standards are, keeping things consistent which is good practice.

Thanks.

Hello

Thank you for the information. We are beginning to write our cocoa famers in our country..

Please advise.

Nancy Kipan

REDS –