Just in Time (JIT) is a powerful tool in lean. However, it is not an easy tool. Using it without understanding the requirements can quickly make things worse. I have written about related topics before, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, Just in Time was often blamed for a lack of material, usually by people who do not understand how just in time works.

Just in Time (JIT) is a powerful tool in lean. However, it is not an easy tool. Using it without understanding the requirements can quickly make things worse. I have written about related topics before, but during the COVID-19 pandemic, Just in Time was often blamed for a lack of material, usually by people who do not understand how just in time works.

Just in Time

The basic idea of Just in Time is that material arrives just when it is needed, in the quantity it is needed, at the right location, and in good quality. Or, more realistically, trying to get close to this target with as little inventory as possible. This reduces your inventory, all costs related with the inventory, and also the waiting times of the inventory and hence the lead time. Overall, this can be very good for your business success. I have written a whole series on Just in Time, but this post will look in more detail at the relation of Just in Time with leveling.

The basic idea of Just in Time is that material arrives just when it is needed, in the quantity it is needed, at the right location, and in good quality. Or, more realistically, trying to get close to this target with as little inventory as possible. This reduces your inventory, all costs related with the inventory, and also the waiting times of the inventory and hence the lead time. Overall, this can be very good for your business success. I have written a whole series on Just in Time, but this post will look in more detail at the relation of Just in Time with leveling.

Inventory

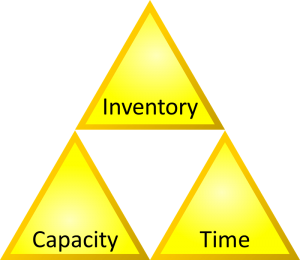

However, inventory does serve a purpose. Besides actually having something to work with, the key purpose of inventory is to buffer fluctuations. It is not the only way to decouple fluctuations, but especially for short-term fluctuations, it is often the most efficient way to decouple fluctuations.

However, inventory does serve a purpose. Besides actually having something to work with, the key purpose of inventory is to buffer fluctuations. It is not the only way to decouple fluctuations, but especially for short-term fluctuations, it is often the most efficient way to decouple fluctuations.

For long-term fluctuations (e.g., seasonality) you can also decouple by adjusting the capacity. This can also be very efficient but usually is a bit slower and takes more time to adjust. If you cannot decouple fluctuation by inventory or capacity, then the system will automatically decouple using time (i.e., your parts, workers, machines, and customers have to wait). There are systems that successfully decouple by letting their customers wait (e.g., the production of commercial aircraft), but for most companies, letting their customers and others wait is quite bad.

For long-term fluctuations (e.g., seasonality) you can also decouple by adjusting the capacity. This can also be very efficient but usually is a bit slower and takes more time to adjust. If you cannot decouple fluctuation by inventory or capacity, then the system will automatically decouple using time (i.e., your parts, workers, machines, and customers have to wait). There are systems that successfully decouple by letting their customers wait (e.g., the production of commercial aircraft), but for most companies, letting their customers and others wait is quite bad.

Just in Time vs. Inventory

Hence, merely eliminating your inventory is very dangerous if your system is not ready for it. Just in Time requires a careful timing of the arriving material when it is needed, with little buffer stocks. But merely reducing the buffer stocks will wreak havoc with your system.

If you want to do Just in Time, there are two ways out of this dilemma. The easy way is to leave everything as it is and just call it a JIT inventory, regardless of how big it is. Obviously, this won’t improve your system, but it makes others (and maybe even yourself) believe it even though it is not. Unfortunately, this is more common than I would like, and I have seen way too many warehouses where I was told, “This is our Just in Time inventory.” No, this is NOT Just in Time; this is just make-believe.

The real way to make Just in Time work is by reducing fluctuations (and, of course, I have a whole series on that topic too). Unfortunately, this is hard, never-ending, Sisyphusian work. Fluctuations will always increase. This is true not only for your shop floor, but also for the entire universe due to the second law of thermodynamics.

The real way to make Just in Time work is by reducing fluctuations (and, of course, I have a whole series on that topic too). Unfortunately, this is hard, never-ending, Sisyphusian work. Fluctuations will always increase. This is true not only for your shop floor, but also for the entire universe due to the second law of thermodynamics.

Even worse, no matter how good you are at reducing fluctuations, once in a while there will be a fluctuation coming along that you could not prevent and that is bigger than your buffer inventory, and you will run out of material or stock.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

Case in point, the COVID-19 pandemic that started in 2019. This messed up supply chains pretty bad, and there were lots of stock-outs all over the place. From masks to computer chips (graphic cards, automobiles, etc.) to toilet paper, there were lots of different shortages.

Case in point, the COVID-19 pandemic that started in 2019. This messed up supply chains pretty bad, and there were lots of stock-outs all over the place. From masks to computer chips (graphic cards, automobiles, etc.) to toilet paper, there were lots of different shortages.

In the press this was often described as a failure of Just in Time and too much optimization of the supply chains. They claimed that industry was cutting costs too much, which caused lots of problems.

Also, there were other factors that impacted many supply chains, from a container ship stuck in the Suez Canal to Britain leaving the European Union to bitcoin mining buying all the graphic cards, etc.

Well, let’s have a look at the alternatives. These articles suggest that more inventory would have helped. Maybe it would have, but at what cost? Let’s take graphic cards. A graphic card costs normally between a few hundred and maybe a thousand+ dollars. If we consider the lower value along the supply chain, lets assume $300 of inventory value for each card. Ten thousand cards would have an inventory value of $3 million. And, 10,000 cards were nothing in the current demand. Yet, simply having the inventory would cost you 30–65% of the inventory value per year. Hence, you would have expenses of $1-2 million per year just to have 10,000 graphic cards in inventory just in case a pandemic comes along. Naturally, these costs would eventually have to be paid by the customer through higher prices for their graphic cards. Hence, everything would become more expensive.

Well, let’s have a look at the alternatives. These articles suggest that more inventory would have helped. Maybe it would have, but at what cost? Let’s take graphic cards. A graphic card costs normally between a few hundred and maybe a thousand+ dollars. If we consider the lower value along the supply chain, lets assume $300 of inventory value for each card. Ten thousand cards would have an inventory value of $3 million. And, 10,000 cards were nothing in the current demand. Yet, simply having the inventory would cost you 30–65% of the inventory value per year. Hence, you would have expenses of $1-2 million per year just to have 10,000 graphic cards in inventory just in case a pandemic comes along. Naturally, these costs would eventually have to be paid by the customer through higher prices for their graphic cards. Hence, everything would become more expensive.

It is all a question of the cost of the inventory versus the cost of a stock-out. Sometimes it may make sense to stock up, and some governments at different times have, for example, a strategic reserve of oil (in the US e.g. ca. 30 days’ supply) or toilet paper (West Berlin stocked 180 days’ worth of toilet paper and other goods during the Cold War). Running out of oil would be worse than the cost of a continuous inventory, and I leave it up to you to judge the need on toilet paper.

It is all a question of the cost of the inventory versus the cost of a stock-out. Sometimes it may make sense to stock up, and some governments at different times have, for example, a strategic reserve of oil (in the US e.g. ca. 30 days’ supply) or toilet paper (West Berlin stocked 180 days’ worth of toilet paper and other goods during the Cold War). Running out of oil would be worse than the cost of a continuous inventory, and I leave it up to you to judge the need on toilet paper.

Well, the (hypothetical) counterargument, then, would be to only build up stock if you need it. D’oh! If industry would have known about the pandemic one year in advance, they of course would have built up stocks. It is always much easier to run a company in hindsight rather than foresight, but usually companies don’t have the luxury of knowing the future, even less so for once-in-a-century (hopefully not more) pandemics.

Nevertheless, some companies by negligence or ignorance made their situation worse. Rather than decreasing fluctuations, they increased fluctuations. Volkswagen (and other car makers), for example, abruptly cut their orders of chips at the beginning of the pandemic, predicting a drop in sales. As it turned out, lots of government assistance increased the cash flow for many, and the car makers now struggle to get enough chips. What the car makers did was the opposite of leveling, reducing orders of chips much more than needed due to a prediction, and then trying to ramp up again. Unfortunately, you cannot turn a wafer fab on and off like a flashlight. Due to long lead times, ramping up production will take quite some time, combined with an overall higher demand for chips.

In one aspect, however, I agree with the news articles on logistics and the pandemic: many supply chains are just way too long. Goods are shipped around the globe multiple times to chase a few cents in savings. Long supply chains increase fluctuations, and you cannot really have Just in Time delivery by ship from Asia to Europe or the USA (unless, of course, you just call any inventory a Just in Time inventory…). Shortening supply chains will help to make companies more robust against global disruptions, no matter if it is a pandemic, a stuck container ship, an embargo, or a war. However, lean manufacturing has always been in favor of shorter supply chains. Toyota tries to have many suppliers close to the final assembly plants. Most Japanese suppliers are within three hours’ drive around Toyota City. Toyota produces a large number of its car engines for the American factories within the USA. If you chase a small saving around the world, you will quickly find that the delays and fluctuations eat up more than you saved.

Overall, Just in Time and lean manufacturing are set up for such situations, and the inventory needs to correspond the impact of a stock-out. Now, go out, level your material flow, adjust your inventories, and organize your industry!

I have been learning a lot about Just In Time Inventory and Lean Six Sigma as a Supply Chain Management Student. This article really helped link the two together. The pandemic is something that has also been a non-stop topic in the supply chain world. Between the blockage in the Suez Canal, the freeze in Texas, shut downs because of COVID, and many other issues, JIT inventory is risky to have. But, as said in the article, having a surplus of inventory “just in case a pandemic comes along” costs companies a great deal of money and may not be worth it in the long run (plus no one wants items o become more expensive). During times where adaptation is needed, having knowledge in Lean Six Sigma can help identify problems, improve performance, and eliminate wastes.

Great post. It’s important to understand each concept/technique in the context of its operation. The lockdowns associated with the pandemic were specifically designed to stop people movement and supply chains. It’s not a reflection on JIT. So what we are feeling the effect of is not really JIT but that of elaborate global supply chains, that people took for granted in normal times, and adopted to save a few cents,

I really enjoyed reading this post, as a student studying Supply Chain currently focusing on Lean Six Sigma. Recently we have been studying JIT as you discussed in this post, and your post really helped me to distinguish between problems with JIT and other issues highlighted by the pandemic. I feel as though many companies have done a poor job adopting Toyotas model of JIT and the need for shorter supply chains is apparent if companies can save money by perfecting JIT this will only truly happen when their suppliers are closer in incase any issues/ disruptions arise, an example being the global pandemic. I look forward to reading more about your thoughts as supply chains try to recover.

Very good article and I totally agree to everything what was written. Another interesting side fact is that Toyota apparently was not forced to shut down factories due to a lack of computer chips. After the tsunami in 2011 they defined strategic parts which were important in order to ramp up production quickly and computer chips were among them. Ever since they have kept a strategic safety stock. Only now the chip crisis have also reached Toyota and they are forced to cut their production.

Many thanks to all for the praise. It is a tricky topic, and, of course, now everybody would like to have the safety buffers, but nobody would like to pay for this if you don’t need them. Figuring out how much buffer you need is a tricky question, since a lot of the risk and fluctuations are hard to quantify.

As a student majoring in Supply Chain Management, I have heard a lot about Just In Time. This article helped me better understand what it is and how that process works. Covid-19 had a very negative impact on companies’ supply chains, especially those who used JIT. I wonder if now companies will be more hesitant to use JIT because of the fear of another pandemic, or even something like the cargo ship getting stuck in the Suez Canal. So many events that have caused disruptions to major supply chains have happened recently, so it may be time for companies to start rethinking using JIT.

As I am currently studying Supply Chain Management in school, just in time (JIT) has been a hot topic ever since the beginning of the pandemic. Recently we have been discussing why it was working well before the pandemic, and what we can do going forward to ensure that companies have enough inventory to last them some extra time. Although storing more materials can cost money, in the long run, it will save you money by allowing you to keep a product flow, and not have hindrances due to supply shortages caused by JIT. It is going to be interesting to see how companies adapt in the post-pandemic world as they seek not only to have efficient supply chains but resilient ones as well.

Thanks for sharing this information on Just in Time manufacturing! I am a supply chain student and have learned about JIT in a few of my classes. I have also heard many people blame the supply issues on JIT, so it is interesting to learn that it is not the main issue. I agree that shortening supply chains could help a lot of these issues and would definitely improve JIT. In the end, sending goods from country to country to save a few cents can end up costing a company more if there are delays or other issues with the shipments.

One of the best parts of being a student studying supply chain management is being able to learn directly from real life examples of the pandemic’s effect on SCs worldwide. In various lectures, we have discussed potential benefits to utilizing a JIT vs staple stock system, as well as issues that may arise (having a JIT system in place during a pandemic). One of the ways to combat this may be to implement a hybrid system, and simply allocate costs and spending so that you are not effectively wasting money on sitting inventory, nor to rely entirely on Just In Time. Shortening supply chains is a rational solution, though I wonder how realistic that will be in today’s age when our world is becoming more interconnected every day. Insightful post!